By Joel Magalnick , Editor, JTNews

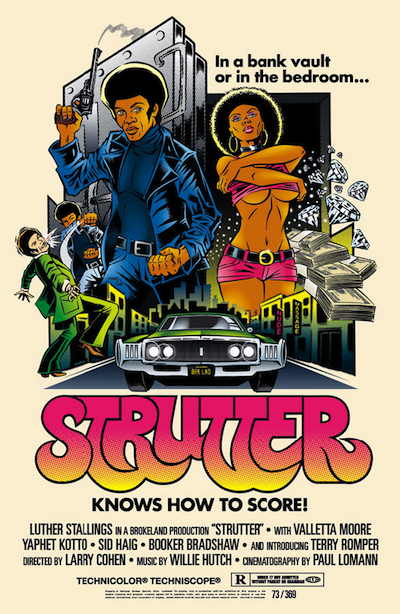

Back in his prime, Luther Stallings was the biggest, baddest, blackest Kung Fu champion and action movie star to walk the streets of L.A. With his co-star Valletta Moore by his side, the man was the definition of cool. Even 30 years later, after the drugs and the drinking and the comebacks gone bad, the star of the infamous Blaxploitation “Strutter” series could knock out a couple of oversized henchman so fast that if you blinked, you’d miss it.

What Luther Stallings couldn’t do was save Michael Chabon’s new novel. In fact, Luther, despite his talents, never made it beyond supporting character in a cast that’s too vast. As I read. And read. And read, I couldn’t figure out what bothered me so much about “Telegraph Avenue” (Harper, $27.99). Then it hit me. This book, it’s like the menu at Cheesecake Factory. It’s got pages and pages of just about anything you’d want to eat, but none of it feels authentic. It’s all oversalted, high cholesterol, and sampled by focus groups. And they’re almost the same number of pages.

These are, admittedly, harsh words for an author who wrote my favorite book of all time, “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay,” and whose 2007 “Yiddish Policemen’s Union” is among my top 10. That an author so imaginative might not be able to top two masterpieces shouldn’t be unimaginable — who talks about Beethoven’s 10th, after all? — it’s that with this go-round, it feels like he’s trying too hard.

Luther’s son Archy is the closest thing this story has to a hero — though a tragic one. Archy and his best friend Nat Jaffe own Brokeland Records, a failing music store on an uncharted desert island between Berkeley and Oakland that sells nothing but vinyl — in 2004, when the record business is suffering and those ubiquitous white headphones have been popping up all over town.

The writing is on the wall now that Oakland native and former NFL star quarterback Gibson Goode, a.k.a. G Bad, the fifth richest black man in America (he owns a zeppelin!) has come back home. City councilman Chandler Flowers III, who’s got his own checkered history with Luther, has just thrown his support behind G Bad to build a Dogpile Thang, his popular chain store geared toward black consumer culture, complete with an expanded vinyl record section, just two blocks from Brokeland.

Naturally, Archy and Nat smell a rat, and their reactions trickle into to their marriages. Gwen, Archy’s about-to-be-estranged wife, and Aviva, an ace midwife who has long suffered husband Nat’s Brooklyn transplant neuroses, are business partners as well, dealing with their own issues. Gwen, 36 weeks pregnant and livid about revelations of her husband’s infidelities, has put her professional partnership and their hospital access in jeopardy following complications during a homebirth.

Then there’s the kids: Julius, Nat and Aviva’s 14-year-old son, has fallen in love with Titus, the 15-year-old son that Archy kind of knew he had, but had not laid eyes on until, well, just now.

Everything up to this point has taken place on the day the story opens. Tired yet?

Also on day one, just before he encounters his “new” son, Archy has his first encounter in years with Valletta. It appears that Luther is back in town, news that Archy doesn’t exactly welcome. Things head downhill from there.

Chabon jumps into the heads of each of these characters, and many others, but so many feel crudely drawn that even toward the end the only character I felt I really knew was the young, heartsick Julius with his unrequited love.

The author writes the language of black Oakland through Archy and the old men who hang out at the record store all day, but Toni Morrison is far better at the dialect, and Percival Everett’s contemporary black fiction (not to mention the laissez faire attitude both he and Chabon try to get across in the writing process) feels much more like the real thing, because it is the real thing.

In the end, though, it’s Chabon who saves his own book. As a writer he is still unique, musical, and a joy to read. In the hands of an amateur, “Telegraph Road” wouldn’t have made it past the literary agent’s desk.

But like the obnoxious advertisements on the pages opposite Cheesecake Factory’s menu items, he resorts to gimmickry — Gwen, grumpy and about to burst, also happens to be a black belt in qigong and catches a teacup flung at her head from close range (never mind that Chabon, breaking the cardinal rule of “don’t write in a gun that you don’t plan to shoot” never gives Gwen another chance to break out her lethal fists); a fundraiser at a Berkeley mansion features a certain African-American state senator from Illinois with his own race for U.S. Senate well underway (this is 2004, remember); a 12-page, single sentence in which Fifty-Eight, Mr. Jones’s parrot, surveys the goings-on in the East Bay upon being set free.

Imagine a climax of this story that’s something akin to the last fight scene of Quentin Tarantino’s “Kill Bill Vol. 1,” a Busby Berkeley-esque scene of synchronized Kung Fu fighters. Which would have made sense, given how much ink Tarantino gets in this book, and given that if you’re going to remove your story from the authenticity of the Blaxploitation era, you may as well give credit to the original homage rather than the real thing. But sorry, not here. All we get is over-sugared cheesecake.

It’ll probably be a good five years until we see Chabon’s next novel. You might be better off waiting.