Explaining Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the Days of Awe, to children is both difficult and simple. Difficult, because deeper levels of spiritual understanding must await a more mature approach; simple, because even very young children can delight in the tastes, sounds and symbols of these days.

Then, as they begin to understand the concepts of being sorry when we do wrong, asking for forgiveness, and trying to be kind and fair, they are learning teshuvah, tefillah and tzedakah — repentance, prayer and justice — at a child’s level. Well-chosen books can help us open all these gates to growth.

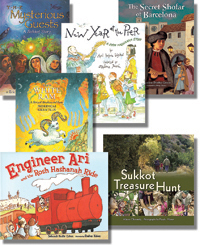

The Secret Shofar of Barcelona by Jacqueline Dembar Greene (Kar-Ben Publishing, 2009, ages 5-9), like Greene’s earlier adventure novels, Out of Many Waters and One Foot Ashore, deals with Sephardic Jews. Set in Inquisition-era Spain, the story tells of Rafael, who is a secret Jew along with his family and many others. When his father, gifted musician Don Fernando, is asked to perform a symphony celebrating the New World, he and Rafael plot to also celebrate the Jewish New Year publicly during its performance. Rafael rehearses the traditional notes of the shofar and plays them as part of the symphony before the whole court, secretly risking all in defiance of Spanish oppression.

Another holiday story enhanced by a historical setting is Engineer Ari and the Rosh Hashanah Ride by Deborah Bodin Cohen (Kar-Ben, 2008, ages 3-7) based on the 1892 opening of train service from Jaffa to Jerusalem. Engineer Ari can’t help boasting to his disappointed fellow engineers about being chosen to take the first train up to Jerusalem. He sets off without even saying goodbye. Along the way, at various stops, he receives symbols of the holiday — apples, honey, rams’ horns and round loaves of bread — to take along, each item representing the products of that area. Shahar Kober’s charming illustrations turn this trip up to Jerusalem into a window on early Israel’s terrain, crops and people. Meanwhile, the closer Ari gets to the city, the more he begins to consider and regret his behavior, thinking about how much he must have hurt his friends. After arriving, he turns the train and himself around, toot-tooting back toward Jaffa to do teshuvah.

Teshuvah at a child’s level is also the focus of the modern and delightful New Year at the Pier: A Rosh Hashanah Story (Dial Books, 2009, ages 6-9) by April Halprin Wayland, convincingly illustrated by Stephane Jorisch. As a former Southern Californian, I recognize the walk Izzy and his family take to Santa Monica Pier for Tashlich. Kids will recognize, too, how hard it is for Izzy to take inventory of all his mistakes and make amends. Only then can he toss bread crumbs for each mistake into the water and start the new year fresh and forgiven.

Believable family interaction, a good sense of community and some lovely language permeate this very now, very real story. Some of my favorites describing the place and process: “Some days sunglasses, some days sweaters. The sound of the shofar and the salty smell of the sea.” And then, as Izzy, the family and friends walk home, they take with them “empty bread bags…and clean, wide-open hearts.”

One of our most difficult Torah stories, the Akedah, is read each year on the second day of Rosh Hashanah (or, in the Reform tradition, on the first). Award-

winning author/illustrator Mordicai Gerstein tackled the death of Moses in The Shadow of a Flying Bird (1994), so it isn’t surprising he was able to find a new viewpoint from which to approach this challenging narrative. Gerstein’s The White Ram: A Story of Abraham and Isaac springs from the legend that in the twilight of the first Sabbath, God made a white ram. This story is based on Midrashic tales speculating that the ram was made for just one purpose, its task to appear when God called to save Isaac by taking his place.

This 2006 work, though beautiful and lyrical, contains a couple of points which may bring some readers pause: First, the ram constantly repeats “I must save the child” and, as is often done, Isaac is presented as a very young boy. Second, while Gerstein ostensibly follows the Jewish tradition which prohibits showing God’s image, he fudges by cleverly and effectively using empty space and clouds to indicate God’s presence. We see hands and, eventually, even a man-like profile of the Lord, clouds for a beard and a flying bird for His dark, dramatic eye. Gerstein did a similar thing in the stunning story about Moses. Whether these points are deal breakers depends upon the reader. The book itself is beautiful.

Leaving Elul, we welcome The Mysterious Guests: A Sukkot Story (Holiday House, 2008, ages 6-10) by Eric A. Kimmel. Kimmel here pays tribute to the Jewish values of hospitality and generosity by invoking the Ushpizin, spirits of the Patriarchs we’re supposed to invite into every sukkah during the holiday. He works with a familiar framework: Two brothers, Eben, wealthy, snobbish and selfish; Ezra, poor, but open-handed and open-hearted to everyone. So, when Abraham, Isaac and Jacob come to town in rags on the eve of Sukkot, at Eben’s magnificent sukkah they are ignored and insulted. Before leaving, they tell a story which includes a special blessing. It begins to take effect immediately, breaking up the party — not to mention the sukkah.

They next go to Ezra’s where, despite their rags, they are welcomed and fed. Asked pleasantly if they have anything to share, Abraham again tells a story, though a very different one. However, it concludes with the exact same blessing: “May this sukkah’s outside be like its inside” And so it was. The poor man becomes a wealthy benefactor and the stingy man “searched his heart and changed his ways.”

A last book about Sukkot by Allison Ofanansky with photos by Eliyahu Alpern, Sukkot Treasure Hunt (Kar-Ben, 2009, 3-8) shows modern Israeli family life in northern Israel with an emphasis on the link between Jewish holidays and the natural world. Aravah’s family are almost ready for Sukkot but they still need the “four species,” lulav (palm), aravot (willow), hadas (myrtle) and an etrog. They decide not to buy these things but to seek them out in the area around Tzfat, where they live. The photographer follows Aravah and her parents during their search, which concludes with their finding an etrog in a most unexpected place.

Hag Sameach!

Magical journeys