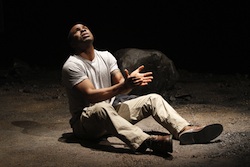

“There is no shortcut to certainty,” says Gbenga Akinnagbe, in character as the solo actor who portrays the stories of 11 Seattle citizens in The Thin Place, a play premiering at Intiman Theatre that runs through June 13.

One of the characters is Isaac, a young Pentecostal African American, who guides the audience through the play as he questions the religious tradition he was raised in as a preacher’s son. As he journeys, Isaac encounters 10 others who question the role of faith, or authority in the case of atheists, in their lives.

The stories are all based on interviews conducted by local public radio affiliate KUOW’s Marcie Sillman with Seattle residents from diverse backgrounds and spiritual traditions. The play is not about the creed of religion each person practices, said Sillman — whether Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Buddhist or atheist. It’s more focused on how people relate to their faith and to other people while dealing with the challenges in their lives.

One Seattleite featured as a character in the play is Tammy Kaiser, who was an employee injured while trying to escape the shooting at the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle in 2006.

“The play is really about moving through and with this crisis of faith and coming out with either a different perspective, or possibly strengthening the one the individual already had,” Kaiser said.

Right after the shooting, Kaiser remembers feeling troubled by all the media attention because of the people who were injured and the nearness to the time of the tragedy. But now, four years later, she is enthusiastic about the opportunities the play creates for people to talk about and question how faith is part of their lives.

The scene in the play dealing with Kaiser’s story portrays her during the shooting and how at that time, she felt the absence of God. The character in the play represents Kaiser’s anger with God after the shooting and subsequent struggle with what her perception of God really is.

“My concept of God changed dramatically because in the moment where I thought I was definitely going to die, there was no God,” Kaiser told JTNews. “God was not what I was thinking about. It was that complete absence of faith that really kind of threw me into a tailspin.”

Since the shooting, Kaiser has left her job at the Jewish Federation and become a chaplain working in lifelong adult learning. She struggles with her faith constantly, but sees this as a healthy way to engage it. Kaiser says many have told her, “”˜Just because something like this happened doesn’t mean you have to question everything in your life.’”

Her response is: “You’re right, but it gives you the opportunity to.”

The others portrayed in The Thin Place grapple with their doctrines regarding faith as Kaiser has. The play’s author, Sonya Schneider, chose Isaac as the main character so the audience could identify with someone whose faith is uncertain and unstable. Isaac first ponders how much he should let faith inform his life when his mother becomes ill after devoting her life to their church community.

With this challenge to his faith in God’s healing abilities, Isaac travels from his home in an attempt to get away from his old church and the recent pains in his life. He suffers repeated setbacks — physically with bouts of seizures and mentally by pondering what Christian behavior and belief in God really are.

“Faith provides a moral compass for many people,” Schneider says. “When you’re exploring and suddenly lose that compass, you want it back.”

Schneider has felt some of these challenges herself. Her mother was Jewish, while her father did not claim a faith tradition. Judaism has had an influence on her life, but there are other pulls as well, such as agnosticism.

“God has never been in question, but faith has,” Schneider says, adding that sitting in a house of worship or at Passover doesn’t make sense to her.

The Thin Place is not about providing answers for its characters or for the public. The challenge for each character is to accept the need for questioning faith and authority.

“I’m content with a question mark,” Kaiser says.

Besides doubt, the play also addresses how people from different religious backgrounds relate to one another. Kaiser says that having a solo actor works well, giving the feel that all the characters, despite their different faith backgrounds, are one.

“There is nothing more spiritual than feeling connected to other human beings,” says Akinnagbe, in character during the performance. This is a challenge several of the characters face, whether learning to see their enemy as a friend, moving beyond past abuses to trust others, or finding acceptance for one’s sexual identity among peers.

“One of my greatest fears for any faith tradition or religious institution,” says Kaiser, “is that an individual will think their way is the only way.”

By bringing Buddhist, Muslim, Jewish, and Christian doctrine and atheism into the same space, the production team seems to affirm Kaiser’s belief. Highlighting common examples of questioning faith within each tradition and within one city also can create a unity between the separate belief systems. It shows that even in Seattle, faith may be present and cohabitate more than is generally assumed.

“We all have the spark of the divine in us,” says Kaiser. “And if we can live together and respect each other as humans, I think that’s as close to God as you can get.”

Briana Watts is a student in the University of Washington Department of Communication News Laboratory.