A classic Jewish tale of love and darkness, S. Ansky’s The Dybbuk has been the crown jewel of Yiddish theater since its first performance by the Vilna Troupe in 1920. Nearly a century and hundreds of performances later, Seattle’s Music of Remembrance will perform the famous play’s long-hidden original score as part of its 13th season this November 8.

Music of Remembrance, a chamber music organization dedicated to honoring the artists and musicians who continued creating despite anti-Semitism and Nazi persecution, holds two major concerts each year. The fall performance commemorates Kristallnacht, the spring, Holocaust Remembrance Day.

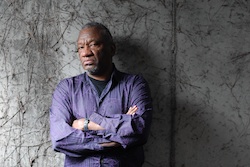

In spite of its immediate and ongoing popularity, The Dybbuk’s score fell victim to the silencing of Jewish art music in the first half of the 20th century. According to MOR founder and artistic director Mina Miller, the goal is “not only to bring to life this original music, but also to bring the story of the play to life through dance.” To this end, Miller is working with acclaimed choreographer Donald Byrd.

“It’s nothing that you’re going to see or hear anywhere else,” she said.

Miller, who is known for pushing artistic limits, unearthed Russian composer and New Jewish School member Joel Engel’s score in a Moscow archives. No known recorded version exists.

Due to growing anti-Semitism and the tragic fate of Russian Jewry, the original music “disappeared into oblivion,” Miller said. “We have resurrected this music.”

Yeshiva prodigy-turned-atheist-turned-Jewish ethnographer Ansky wrote The Dybbuk after touring Eastern Europe’s Jewish communities, where he observed folk life and collected folktales. The story recounts a young man who, after reaching a spiritual height, drops dead and possesses the body of his beloved, whose father wrongly swore her to another (richer) man. The dybbuk (from the Hebrew l’davek, to cling) is an ancient Jewish concept that reached its glory in Eastern European folk life. Ansky’s telling picks up on dominant themes in Jewish lore: Broken promises, the all-consuming power of unrequited love, wonder-working rabbis, trials and the struggle between spiritual and material worlds.

“Symbolically, it’s been seen as the struggle of the soul between heaven and earth,” said Miller. Despite the Jewish context, Miller points out that such folktales “are really richly layered morality tales that have universal resonance.”

Donald Byrd agrees.

“It’s about obsession,” he said. “I’m fascinated by obsession, so that probably is the thing that’s driving me the most.”

Byrd, who has his own dizzying list of critical accomplishments, is working with MOR for the second time in his career. Byrd was drawn to Miller’s mission of rekindling the memories of artists whose lives and artistic contributions were cut short by the Holocaust. He was impressed by “not only what she was doing, but how she was going about doing it,” he said. “As an artist I often wonder…if I died today would anybody even known what I’d done?”

Byrd brings a modern sensibility to this old world play.

“I think it’s wonderful to tell the old story, but what is it that runs through the old story that people connect with today?” he asks.

To him, the play expresses transcendent themes, such as self-determination and possessive love.

“The biggest struggle in learning how to have a mature relationship is learning that you don’t own someone that you’re in love with,” Byrd said. In one way, the play teaches about “how to love with a loose embrace.”

How these elements will come through dance is hard to pin down.

“Visually, it’s a three-person distillation of the essence of the story,” Byrd said.

Byrd is not the first to choreograph this dramatic piece. In the 1950s and ‘60s, Martha Graham dancers Pearl Lang and Mary Anthony performed it. Leonard Bernstein collaborated with Jerome Robbins to create a ballet in 1974.

Byrd describes the music as “mysterious — and not scary — but otherworldly.” Miller emphasizes that listeners don’t have to be “high brow” to relate to the music. It is accessible to all age groups.

“So much of it is based on Jewish folk melody that they heard in the shtetls,” she said. “It’s really lively Klezmer stuff.”

By focusing on Jewish folklore this season, MOR embraces Eastern European Jewry’s event horizon.

“Part of the Holocaust is exploring Jewish identity,” Miller said — that is, the identity the Nazis sought to destroy. Coming into contact with that culture means delving into folklore.

“When we learn something about the Jewish folklore at the time, it tells us about the world that was soon to be transformed,” she said.

In addition to The Dybbuk, MOR’s fall performance includes Alexander Krein’s Hebrew Sketches, no. 2, opus 13; Mikhail Gnessin’s Piano Trio, opus 63 (“Dedicated to the Memory of Our Lost Children”); and Dmitri Shostakovich’s From Jewish Folk Poetry, opus 79.

Regarding her musical ensemble, Miller said, “They are the best in the universe, without exaggeration.”

Many performers are Russian émigré artists now playing the music they were once not allowed to play. Miller emphasizes that November’s concert goes beyond the Holocaust by paying special tribute to Russian Jews.

Miller recited The Dybbuk’s opening lines: “Why, oh why, did the soul plunge from the utmost heights to the lowest depths? The seed of redemption is contained in the fall.” They are words that represent the play, but that continue to resonate with human history and the path of so much Jewish art music that MOR seeks to preserve and resurrect.

Dybbuk resurrected