By Leyna Krow, Assistant Editor, JTNews

Aside from a very legitimate concern about locusts, it may, at first glance, be difficult to see many similarities between fruit pickers living in Immokalee, Fla. and the Israelites who fled Egypt 3,000 years ago. However, according to journalist John Bowe, these two groups of people aren’t as different as they might appear. The common thread: both know what it’s like to be enslaved.

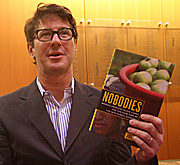

Bowe, the author of Nobodies: Modern American Slave Labor and the Dark Side of the New Global Economy, presented stories of his research into the problem of modern slavery in the U.S. at a talk at Hillel at the University of Washington on April 16, three days before the start of Passover.

The timing of the event was no accident, according to Hillel at the UW’s Greenstein Family Executive Director, Rabbi Will Berkovitz.

“We can’t enter this season of freedom without acknowledging that slavery is not a past reality, tucked neatly into the pages of the Bible,” Berkovitz said in his introduction of Bowe.

Hillel’s social justice coordinator, Robert Beiser, said he considers Passover the perfect time to get Jews to think about the impact their choices have on the freedom of others.

“Hosting this visit by John Bowe is a way to emphasize our Hillel’s commitment to encourage students and young adults in their pursuit of justice, and to highlight the Jewish obligation and connection to the issue of modern slavery,” Beiser wrote in an e-mail concerning the event.

Bowe’s book focuses on three different cases of slavery occurring in the United States.

Nobodies opens with the case that first caught Bowe’s attention more than seven years ago, and about which he wrote an article for the New Yorker: the tale of Mexican immigrants working for a labor contractor in Florida. The contractor had paid for their transit to Immokalee, and then forced them to live in squalid conditions while they worked off their debt picking fruit. Nicknamed “El Diablo,” the contractor had routinely threatened his employees with violence to keep them from leaving. The workers, most of whom were in the United States illegally, had no idea of their rights or who to go to for help.

“They weren’t really locked up,” Bowe said. “But they were made to believe that if they left, they would be hurt or deported.”

In 2001, El Diablo and two of his associates were arrested and tried with conspiracy, extortion and possession of firearms. Their attorneys argued that the labor contractors should not be held responsible for the poor treatment of their employees. Instead, the blame ought to fall on the juice corporations for whom the fruit was being grown. The citrus company executives denied any knowledge of the mistreatment of the pickers, however, claiming that the pickers were El Diablo’s employees and not their own. Ultimately, all three contractors were sentences to 12 years in prison.

The second case study focuses on John Pickle, owner of a company that makes pressure tanks used by oil refineries and power plants. Pickle, looking for a way to save his company money, began hiring workers from India who came to live on his company’s property in Tulsa, Okla. and worked for $3 an hour. These men were housed in dilapidated barracks and granted limited access to the outside world by Pickle, who believed that just by employing these men in the United States, he was doing a good deed.

“His main thing was that he was just trying to help these guys,” Bowe said.

Bowe grew animated as he talked about the Pickle case. The tale is peppered with accounts of a gothic Halloween party, a high-speed car chase, and a vision-seeing Pentecostal minister.

“You think it’s going to be dry, human rights stuff, but it’s actually total insanity,” Bowe said of his book.

Bowe finishes off Nobodies with the story of garment workers living on the island of Saipan, a U.S. commonwealth north of Guam. The workers there manufacture products that say “Made in America” on the labels but work for far less than the American minimum wage.

Here, according to Bowe, is where the greatest difficulty arises for his readers. How, they want to know, can they ever be certain that the products they are purchasing were produced in a responsible manner by employees who are treated fairly and pair proper wages?

His honest answer to this predicament: “You’re stuck. The notion that there’s any way to personally break free of this is unrealistic.”

Rather than trying to only buy fairly made products, Bowe suggests writing letters and making phone calls to corporations suspected of unfair labor practices and asking them who’s working for them, and how much they are being paid.

“Just harass them. Bother them about this stuff,” Bowe said. “I think harassment is great.”

He also recommended supporting organizations like The Campaign for Fair Food and the Student/Farmworker Alliance as well as simply taking 10 minutes a day to think about where the things we buy are coming from.

“You read the Torah and you think it’s so far removed from the way we live now, but it’s not,” Bowe said. “There are things going on today, in this country, that are just unbelievable.”