By Gigi Yellen-Kohn , JTNews Correspondent

As a college English major, I learned the prologue to the Canterbury Tales. Chaucer’s 14th-century language invokes the onset of springtime — April with “his showers sweet” — as an inspiration for pilgrimages.

Nowadays, catching up on what I didn’t learn in college, I head out on my own religious journey at this season. Unlike Chaucer’s characters’ travels, my pilgrimage takes me no farther from home than a Shabbat afternoon seat in my nearby synagogue and the back pages of my siddur.

This is the season when Jews traditionally learn Pirke Avot. Some read a chapter a week all the way through the summer up to Rosh Hashanah. But some, like the group I attend, just go from Passover to Shavuot.

What is Pirke Avot? And why is Rivy Poupko Kletenik, JT News columnist and Seattle Hebrew Academy head of school, teaching it every Shabbat afternoon?

“I loved my father’s books,” she says, calling her resources “friends that I take out every year.”

The books and the love of teaching are now an inheritance from her father, the late, learned Rabbi Baruch Poupko, who in his last years enjoyed sitting in and watching his daughter’s Shabbat afternoon classes.

“There’s such a wealth of strong opinions,” she says of the many commentators she brings into these springtime spiritual explorations. “Psychological, Chassidic, academic, even Christian scholars.”

Pirke Avot has landed so deeply in our everyday wisdom that its origins in the early years of the Common Era — ca. 200 BCE to 200 CE — have become almost irrelevant:

“Who is wise? One who learns from every person…. Who is rich? One who is happy with what he has.” (Chapter 4, v. 1)

“If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, what I? And if not now, when?” (1:14)

“Find yourself a teacher. Make yourself a friend. Judge everyone favorably.” (1:6)

“There are four character types: “˜mine is mine and yours is yours,’ an average character…; “˜mine is yours and yours is mine,’ an unlearned person; “˜mine is yours and yours is yours,’ a very pious person; “˜yours is mine and mine is mine,’ a wicked person.” (5:13) (Translations paraphrased from Artscroll siddur)

“Pirke Avot” is often translated as “Ethics of the Fathers,” or “Chapters of the Fathers,” but that title turns out to be misleading. In fact, a dozen years ago, a collection of Jewish-mother wisdoms called “Pirke Imahot” mirrored the name, but missed the history. Pirke Avot is indeed a collection of memorable sayings by men who presumably were fathers, arranged in chapters (“Pirke”). But the title engages us in classic Jewish word play.

Does “avot” here really mean “fathers”? Sayings of great rabbis? Actually, as we were reminded in the first class this year, the word “avot” usually means just the forefathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. So the teachers whose sayings have been collected in this classic book — this part of the Mishna — aren’t “avot”? In fact, maybe the title doesn’t refer to people at all.

“Av,” plural “avot,” often means the essence, the fundamental, the original. So these chapters of sayings by teachers from a foundational time in Jewish history are actually “chapters of fundamentals,” — basically, the ethical bases for a good life, as passed down from teacher to teacher, collected in the critical years of Jewish development that surrounded the 70 CE destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.

Challenged from within by the nascent Christian movements, and from without by the cultures we learned in college to call “classical,” the voices of those who received the tradition’s wisdom remain alive in Pirke Avot.

My own father’s remembered voice comes alive as I write this. Dave Yellen was a kid in 1920s Beaumont, Texas, one of five sons of a learned immigrant father, the town’s shochet, known as “the Reverend L.M. Yellen.” What I know about our family’s history of learning at this season is that the little boy who became my dad so badly wanted to go play baseball on springtime Saturday afternoons that he taught himself how to start crying. His soft-hearted father fell for it, and, I’m glad to report, it did his son’s Jewish identity no harm.

But the story speaks to the spirit of the season. The weather improves, the days grow longer. And it is that very spirit that placed the study of Pirke Avot into Sabbath afternoons all over the Jewish world.

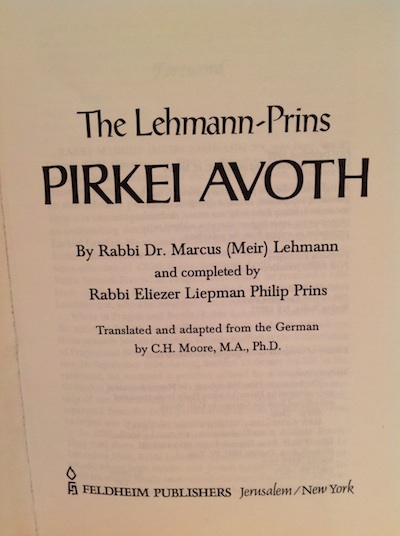

Perhaps, considering some of the tales of Chaucer’s pilgrims, a lot more than a kid’s baseball game was at stake. As it says in this intro from the Lehmann-Prins Pirke Avoth, part of Rivy Kletenik’s treasured collection:

When nature awakens from its winter sleep, field and meadow reflect the beauty of spring, the stately fruit trees gladden the eyes and the heart with their splendid blossoms, then man, too, feels a stirring of new life and hidden desires. In this season, therefore, as a way of restraining those awakening passions, the Sages enjoin us to read the Chapters of the Fathers, a remarkably fine collection of ethical teachings…. These ethics differ considerably from those of other nations, for the latter are man-made, whereas Jewish ethics emanate from God.

Indeed, the compilers of Chapter 1:1 of Pirke Avot trace the lineage of Jewish wisdom from Moses, hearing it straight from God on Sinai, directly to their own teachers.

The often-quoted Hillel, he of the “If I am not for myself, who will be for me” verse, gets the last word here. Not one of his many Pirke Avot quotations, but, conveniently, his famous voice from that part of the Talmud titled Shabbat. Rabbi Hillel is asked to sum up the whole Torah on one foot. His reply works equally well for a good sport or a good student: “What is hateful to you, do not do to someone else. The rest is commentary. Go and study.”