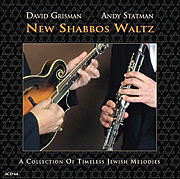

Funny, I took the CD New Shabbos Waltz, David Grisman and Andy Statman’s sequel to their Songs of Our Fathers, for a “Jewish” album, but the digital know-it-all that popped up on my screen calls it “Country.” Indeed, the title track, all twangy mandolin, slide guitar, and thumpy bass, is definitely a country-style waltz. And definitely “Shabbos?” Yep: the dean of Brooklyn’s buttoned-up Chaim Berlin yeshiva composed this melody for the classic Shabbat-welcoming poem, Lecha Dodi.

As we head toward the turning of the Jewish year, assessing what’s gone before, and what’s in store for us, I’ve been listening to this album, released about a year ago. And I’ve been thinking a lot about Andy Statman — musician and Jew.

Statman played Seattle nine years ago, touring in support of his jazz albums The Hidden Light and Between Heaven and Earth. Not everybody at the “J” appreciated watching the star performer play his clarinet with his back to the audience, but Statman did just that, like a leader of Jewish prayer. Some congregations get to see the face of the rabbi or cantor during davening. But the Orthodox way is for everybody to face east. And Statman is an Orthodox Jew.

He wasn’t always. On his Web site (www.andystatman.org), you can read what Grisman, his first mandolin teacher, has said about the religious journey of this American roots musician. Grisman told the Jerusalem Report’s Sara Eisen, “It was the music that led Andy to observance. And then he got deeper into the music by going deeper into its source.”

As the story goes, Statman was a teenager from Brooklyn, besotted with bluegrass, when he sought out Grisman in the late ‘60s Greenwich Village music scene. That started him on a road that has led him to accolades as a true American roots musician, a leader in the bluegrass revival. To his plucked-string expertise, he added woodwind skills, discovering, along the way, a mentor in the late Dave Tarras, the immigrant generation’s acknowledged Klezmer master. From here came Statman’s album (with Zev Feldman) Jewish Klezmer Music, a seminal recording of the mid-1970s’ Klezmer revival.

Klezmer has come a long way in the 30-plus years since then, and so has Statman’s music. For that matter, so has “roots” music in general, including the classical kind. During the decade of Klezmer’s revival, period-instrument ensembles, with their painstaking efforts to re-create music “as Bach (or Beethoven, or whoever) would have heard it,” were all the rage. A taste for “the real thing” supplanted earlier preferences for “the new and improved.”

But these purists, too, have mellowed. Klezmer has blended into the diversity of American life as one of many musical roots musics. The purist revivals have spawned new children, world-aware musics, where Klezmer meets Africa meets Brazil meets India.

During the coming month, our High Holiday prayers will include memorial services. We will acknowledge that our lives are “Like the grass that withers, like the flower that fades….” And such is our music: blossoming, seeding new gardens, sprouting new hybrids with old strengths.

New Shabbos Waltz has its pleasures both nostalgic and educational: I enjoyed Statman and Grisman’s two mandolins intertwining with guitar on the familiar Yiddish lullaby “Oifen Pripitchik” (“By the fireside”). Statman’s clarinet gently nestles a verse against lacy plucked strings. They do some Carlebach, they do “Yerushalayim Shel Zahav,” and they include David Sears’s insightful notes, which not only credit the sources but hint at the spiritual world lurking in those High Holiday prayers. It’s an excellent album.

But Statman the jazz man still captures my soul best. Sitting on a sunny Seattle porch with an old friend, catching up in the way we do at this season, I had to say that, after the down-home delights of New Shabbos Waltz, I returned to The Hidden Light, and found its otherworldly imagination liberating.

May the New Year be filled with musical flowerings, from the roots of our traditions to the freedoms of our best creative work.

A season of roots music