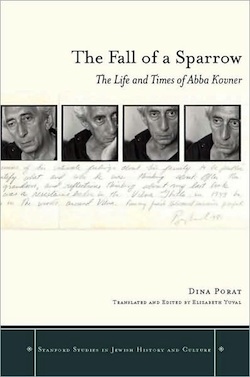

The Fall of a Sparrow: The Life and Times of Abba Kovner , By Dina Porat; translated by Elizabeth Yuval (Stanford University Press, 2009).

Abba Kovner — ghetto resistance commander in Vilna during World War II, leader in the Brichah movement that brought the remnant of European Jewry to Palestine, major Hebrew poet, designer of Jewish museums — was at the storm-center of Jewish history from 1939-49, a decade that determined his subsequent 40 years in Israel. Yet most American Jews first became aware of him through Hannah Arendt’s reports on the 1961 Eichmann trial. She wrote that the great “dramatic moment” of the trial was Kovner’s account of how German officer Anton Schmidt had helped Jewish partisans with forged papers and military trucks, and “did not do it for money.” Those two minutes of testimony were the first and last about a German in the entire trial; they were “like a sudden burst of light in the midst of impenetrable, unfathomable darkness” and prompted Arendt to think “how utterly different everything would be today in…all countries…if only more such stories could have been told.”

This glimpse of Kovner may have given Arendt’s readers the impression that he was an early promoter of the (mischievously misleading) notion that wartime Europe was teeming with Righteous Gentiles. Nothing could be further from the truth. From 1945-47, Kovner alienated many Jews by his project of revenge against Germany and its collaborators, which was required because “the idea that Jewish blood can be shed without reprisal must be erased from the memory of mankind.” Like every other aspect of his life, this episode is fully described in Dina Porat’s splendid book, at once biography and history. It is the most important point of entry into Kovner’s world since Seattleite Shirley Kaufman’s book of poetic translations, A Canopy in the Desert (1973).

Kovner was a paradoxical figure. In a famous speech of December 31, 1941, by which time thousands of Lithuanian Jews had been murdered, and in subsequent calls to arms, he exhorted members of Vilna’s Zionist youth groups: “Let us not go like lambs to the slaughter.”

But when the image of European Jews passively going like cattle to slaughter became a cliché of small Jewish minds in Israel and America, he declared repeatedly: “I never thought a woman who had her child taken out of her arms had gone like a sheep to the slaughter.”

When the war ended, he was fiercely critical of Jews who wanted to rebuild their lives in the continent that had just spat them out: Jews should not settle in a graveyard, he said. Yet when he came to Israel, he redirected his anger at Israelis who were both ignorant and contemptuous of Diaspora Jewry, failing to understand that there is no Jewish future without rootedness in the past. He believed, passionately, in “negation of the Diaspora,” but founded and organized the famous Beit Hatefutsot (House of the Diaspora) Museum in Tel-Aviv, dedicated to the proposition that Diaspora Jews were a dispersed, but not dismembered, people. He was a lifelong member of the left-wing and atheist Hashomer Hatzair movement and Mapam Party, but he rejected the movement’s commitment to international class solidarity in favor of his overriding concern: The survival of the Jewish people.

Kovner was a man of prophetic vision. He was the first to declare as fact the planned destruction of European Jewry. He instinctively sensed that the apparently futile armed resistance to Nazism in Vilna and Warsaw would have its effect not in Europe but in Israel, because nothing done for the sake of justice is, in the long run, useless: “Israel was born in the last bunker of the ghetto,” he said.

Kovner also began, planned, and provided the impetus for the exodus of European Jewry to eretz Yisrael. What for many years seemed the most quixotic of all his ventures, the pursuit of vengeance against Germany, was based on a foreboding that now seems far less outlandish than it did 60 years ago. He believed that vengeance was not only repayment for the past but also a warning for the future — without revenge there would be a second Holocaust. When he learned of the existence of atomic weapons, he wanted them for Israel, to put the world on notice that “those who survived Auschwitz could destroy the world. Let them know that! That if it ever happens again, the world will be destroyed.”

As the international noose today tightens around Israel’s throat, and the umbrellas go up in Europe and also Washington, these words may seem less extreme than they once did.

Edward Alexander is co-author, with Paul Bogdanor, of The Jewish Divide Over Israel: Accusers and Defenders (2006). His most recent books are Lionel Trilling and Irving Howe: A Literary Friendship (Transaction, 2009) and Robert B. Heilman: His Life in Letters (U. of Washington Press, 2009).