On his way to becoming a perennial All-Star in the mid-1950s, Cleveland Indians clean-up hitter Al Rosen received more than his share of barbs from opposing dugouts and the stands.

All these years later, the slugging Jewish third baseman recalls how he distinguished casual insults from malicious slurs.

“There’s a line where you can accept it because you know it’s not right but it’s not that offensive,” he says. “It’s the moment that it becomes offensive that you make a decision, and I’m sure there’s not a lot of forethought to this, but the decision is, “˜I’m going to stop this right now because if I don’t it’s going to go on and on and on.’”

Rosen makes a memorable appearance in Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story, Peter Miller’s entertaining and surprisingly thoughtful documentary about the relationship between the national pastime, an immigrant population and their assimilated sons and daughters.

Jews and Baseball, which boasts a first-rate narration written by New York Times sportswriter Ira Berkow and read by Dustin Hoffman, and an ultra-rare interview with Sandy Koufax, screens as part of the AJC Seattle Jewish Film Festival.

Rosen wasn’t raised with any formal training in Judaism, he said in an interview during the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival last summer, but he knew who he was. Actually, growing up in the 1930s in a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Miami (where Little Havana is today) with no other Jews, there was always some kid to remind him.

“You’re picked on, you’re made fun of, you’re the butt of jokes, and unless you assert yourself soon and often, you soon become cast aside,” Rosen relates. “Well, I was never one to be cast aside.”

That’s not false bravado. Even at 86, the wiry Rosen gives off the vibe of a man who won’t be pushed around. As he describes his adolescence, it’s easy to see why he wasn’t hesitant to use his fists to silence an anti-Semite in the minors or even after he reached the big leagues in 1947.

“Some kids are bigger than others, and they want to be bullies,” he notes. “And sometimes you have to know that you’re not going to win, but you have to take on the bully. That’s what happened more than once in my growing up in the southwest section of Miami.”

Rosen came within one hit of the elusive batting Triple Crown in 1953, and garnered the American League MVP award in a unanimous vote. But bothered by injuries and livid at the way Indians general manager (and Detroit Tigers legend) Hank Greenberg treated him—cutting his salary after the 1954 season and trading him to Boston after the ‘56 campaign—Rosen retired at the age of 32 rather than start over in a new city.

Jews and Baseball suggests that Greenberg was tougher on Rosen, a fellow member of the tribe, than he was on any other Tribe player. When I bring up his predecessor’s name, Rosen only says, “Greenberg and I were not friendly.”

He does credit Greenberg with being the first great Jewish ballplayer, and for inspiring other Jews to enter the game. But Rosen attributes the decline in overt anti-Semitism to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948.

“Once the Jew began to fight, people realized the Jews were not just shopkeepers, nor were they just accountants or doctors or lawyers or musicians,” Rosen declares. “I think there was a metamorphosis that took place. All of us who were in [public] life benefited from that.”

Speaking of fighting, Rosen was longtime teammates with Larry Doby, who broke the color barrier in the American League two months before Rosen was called up.

“I don’t know that Doby was of any help to me as a Jew or I was any help to Doby as a black man,” Rosen says, before recounting an incident in Texas involving a cabbie who refused to drive the black player.

“I got out of the cab and told him he was going to take us and he said, “˜No, I’m not,’ and I grabbed him and punched him,” Rosen says. “I think that sort of resolved Doby’s feelings about how I felt about him.”

Rosen returned to baseball in the late 1970s as president of the Yankees after his old friend, George Steinbrenner, bought the team. Rosen was also a successful GM with the Houston Astros and San Francisco Giants, and he continues to follow the game and hold strong, well-considered opinions.

If one word could be used to describe Al Rosen, it would be character.

“I wore my feelings on my sleeves,” he confides. “I always felt that I want to conduct myself that, if I were walking down the street, one Jew could look at another Jew and say, “˜He’s a mensch.’ That was sort of ingrained in me.”

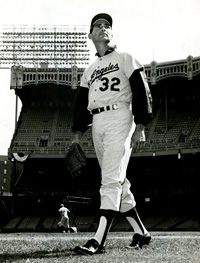

Former ballplayer Al Rosen still slams line drives