By Basya Laye, other

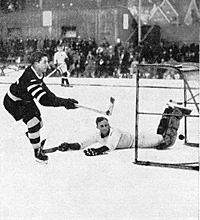

In the rush to celebrate the upcoming Olympics, local residents, Jewish community members and tourists alike are being offered an opportunity to explore and learn from a particularly dark era in the Games’ history. Coinciding with the 2010 Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Games, the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre is presenting two new exhibits: “More Than Just Games: Canada and the 1936 Olympics” and “Framing Bodies: Sport and Spectacle in Nazi Germany.”

More Than Just Games will present an overview of the 1936 Winter and Summer Games in Germany, which have become known as the “Hitler Olympics.” VHEC promotional materials state that the exhibit “will look at the use of propaganda during those Games, offering insight into the Nazis’ anti-Semitic and exclusionary policies, Canada’s involvement in the international boycott debate and the experiences of individual athletes.” Both exhibits feature newly commissioned academic research about Canada’s participation and archival materials, providing a contrasting historicity against the backdrop of Vancouver’s 2010 motto, “Celebrate the Possible.”

Dr. Richard Menkis, associate professor of classical, Near Eastern and religious studies at the University of British Columbia, and Dr. Harold Troper of the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto, were commissioned by VHEC to research and write More Than Just Games. In an interview with the Independent, the professors provided context around the 1936 Games and clarified the genesis of Nazi Germany’s successful bid to host both Games that year.

“Germany was awarded the Games before the Nazis came to power,” said Menkis and Troper. “At first, Hitler had little interest in the Olympics, seeing them as a disgusting example of cosmopolitanism. He was, however, convinced by his minister of propaganda that they could be a wonderful propaganda ploy at the international level, as well as a “˜lesson’ in the racial superiority of the Aryans (because he expected German athletes to excel) directed at the German people. He especially wanted the Summer Games to be a spectacle, and had a direct hand in deciding on the look of the Olympic stadium.”

Menkis and Troper also bring attention to the individual athletes that expressed opposition and/or participated in boycotts in protest of Nazi policies, specifically highlighting the cases of “boxers Sammy Luftspring and “˜Baby’ Yack, as well as the high jumper Eva Dawes.”

Both “Luftspring and Dawes would have been serious contenders for medals at the Games,” they explained.

The professors also investigated the Jewish community’s response at the time.

“The “˜organized’ Jewish community — mostly Canadian Jewish Congress — tried to mobilize public opinion against participating in the Olympics. This was not their only boycott movement — they mounted a campaign for an economic boycott of German goods.”

The exhibit will highlight the left’s opposition to the Games. Menkis and Troper stressed the significance of this protest and the conversation it generated in the media. “The left also supported a boycott of the games. They reacted with horror at the complete repression of the left in Nazi Germany. You can see the fury of Canadian communists and socialists in the newspapers of the time. Some of the editorial cartoons are in the exhibit, as well as editorial cartoons from the Jewish press.”

The professors emphasized that boycotts did have some effect at the time and they stressed the importance of not keeping silent in the face of a repressive regime: “Without the boycott campaign, Nazi Germany would have had a completely “˜free ride’ in the Canadian press,” they wrote via e-mail. “That is, the Nazis would have had even more success than they had in creating the illusion that it was just another regime that wanted to cooperate with the family of nations.”

Both Menkis and Troper hope that visitors to the exhibits will leave with an expanded historical view of the Olympics and be able to critically consider the messages disseminated vis-Ã -vis 2010.

“We can appreciate the incredibly hard work of athletes to prepare for the Games, and understand their wish to excel and to represent their countries. What is much harder to take are the ways that Olympic officials in Canada turned a blind eye to the protests in Canada and made their decision to participate behind closed doors, and the ways in which Olympic officials chose to ignore the signs of complete violations of political and human rights taking place in Germany. It would be nice to think that there is greater transparency in making these decisions now, and that Olympic officials can see through deception and act accordingly.”

In the process of conducting the research for the exhibit, Menkis and Troper were especially enthusiastic about one find in particular. “One of the wonderful discoveries of this research was the reporting of Matthew Halton for the Toronto Star. He was based in London in the 1930s and visited Berlin twice in 1933, and attended both the Winter and Summer Olympics. He spotted the brutality of the Nazi regime early on and, when the Nazis “˜toned down’ the anti-Semitism just before the Winter and Summer Games, he would have none of it, knowing that the Nazis were only suspending the brutality, and not ending it.”

The companion exhibit, “Framing Bodies: Sport and Spectacle in Nazi Germany,” explores the relationship between athletics, politics and visual culture during the 1936 Games.

A quick perusal of the archives on the International Olympic Committee’s Web site (olympic.org) indicates that a “teaching moment” is a necessary addition to the historiography of this chapter in Olympic lore. On the “More About” link on the 1936 Summer Games Web page, the IOC highlights Jesse Owens, an African-American track-and-field athlete who won several gold medals in that year’s Summer Olympics. It reads: “The Berlin Games are best remembered for Adolf Hitler’s failed attempt to use them to prove his theories of Aryan racial superiority. As it turned out, the most popular hero of the Games was the African-American sprinter and long jumper Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals in the 100m, 200m, 4x100m relay and long jump.” The Web page continues: “The 1936 Games were the first to be broadcast on television. Twenty-five television viewing rooms were set up in the Greater Berlin area, allowing the locals to follow the Games free of charge.”

No mention of Nazis or of controversy of any kind appears on the IOC’s 1936 Winter Games Web page.

Basya Laye is assistant editor of the Jewish Independent newspaper where this article originally ran, Oct. 9, 2009.