Slate Magazine music critic Jody Rosen admits that his first historical Jewish music compilation, Jewface, is quirkier and distinctly separate from his earlier and more conventional work, White Christmas: The Story of an American Song, a book about Jewish American musical icon Irving Berlin.

But he was excited that day in 1994, when, at the British Library in London, he discovered the first of what would turn out to be hundreds of pages of sheet music that he would recover over the next 10 years, written by turn-of-the-century, Tin Pan Alley Jewish comedic vaudevillian performers, including Berlin.

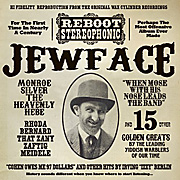

This newly redeemed collection of 16 “Jewish minstrelsy” songs, recorded mainly in New York City between 1905 and 1922, depicts a highly evolved Jewish comedic culture replete with self-deprecating humor, Jewish racial stereotypes, and American assimilation fantasies.

Rosen spoke, showed film clips, and presented images of the sheet music he found on the evening of Thursday, March 13, in the Downstairs Space at Town Hall in Seattle. The event was sponsored by Nextbook.

“I thought this was hilarious, and when I began to look more deeply, realized that this was an entire genre,” Rosen told JTNews from his home in New York City.

Rosen found the documents while in London completing research for a master’s degree in Jewish history at the British library.

“Today, these songs seem quite offensive and incendiary, but they really were the mainstream of American popular culture in the first two decades of the 20th century,” he said.

Some critics say they would rather see songs like “When Mose With His Nose Leads the Band,” or “Cohen Owes Me 97 Dollars” (written by Berlin) buried in historical archives.

But Rosen loves them because they present an aspect of Jewish history that he says isn’t as “pretty” or “decorous a picture as what is normally taught in Hebrew school.”

“At that time there were a lot of comic aviation songs and the Jewish-themed version was I want to be an “˜Oy, Oy, Oy-viator,’” said Rosen. “This was Jewish minstrelsy. These songs are ethnic variations on the caricatures found most prominently in Blackface numbers, but all of them were performed on the vaudeville stage, by what were called ethnic impersonators or ethnic comedians.”

According to Rosen, this tradition included send-ups of Chinese songs, Red Indian songs, Italian, or “Wop” numbers, in addition to Blackface, where, in his opinion, black Americans bore the brunt of some of the harshest theatrical slander. However, Rosen named the compilation CD Jewface, as a variation on the name for the classic Blackface performers of the time.

More formally, the music is referred to as Yiddish or Hebrew dialect songs, and stars of the vaudeville stage at that time like Sophie Tucker, Al Jolson and Fanny Brice sang many of them.

The Jews who performed these ethnic ditties were also satirizing themselves, said Rosen, but unlike the blackface minstrels, they were also making money from it. Some of the more prominent Jews had begun to manage, own and profit from the vaudeville circuit and were becoming heavily involved in the song publishing industry.

“This was the era of the melting pot,” said Rosen. “If your group was getting sent up on stage, you could be pretty sure that the other guy’s group was about to be sent up when the next act came on stage. So…there was kind of a rough democracy of caricature — sort of like a hazing.”

The album was produced and released by Reboot Stereophonic, a record label headed by three of Rosen’s friends and partners: David Katznelson, a former executive at Warner Bros. Records; Josh Kun, associate professor of Communications in the Department of American Studies and Ethnicity at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California; and Courtney Holt, former head of new media and strategic marketing for the Interscope Geffen A&M record company.

Reboot Stereophonic finds and produces “lost Jewish pop music that tells different kinds of stories about music and Jewish history,” according to their Web site.

Jewface fits the form.

“One of the things I like about the Jewface story is that it’s something a little more complicated,” said Rosen. “It’s Jews who are propagating these stereotypes. It’s like re-appropriating the slander.”

Most of the performers in vaudeville at the time didn’t record these songs, according to Rosen, because recordings were not that common — and definitely not profitable. The few songs of the early 1900s that were recorded were preserved on wax cylinders.

For entertainment, people either went to the local theater to see live vaudevillian acts, including Blackface and Jewish Minstrels, said Rosen, or they bought the sheet music.

“There’s vastly more sheet music than there were recordings of what I call “˜Jewface’ songs,” Rosen said. “There were a few records made but there were hundreds and hundreds of songs that were published.”

Rosen, who was raised in New York and Boston, cites his love for his grandmother as the catalyst for his attraction to this music. He realized that the songs captured a part of her experience as a Jewish American whose parents had assimilated and who had cast off their old-world Jewish identity to create something new.

“Because I loved my grandmother so much, I wanted to explore where the songs came from,” he said. “But I also love the songs because of the wonderful melodies and very witty lyrics. They are very compelling voices. A lot of songs are just funny and the music itself is great and catchy and fun to listen to.”

Is that Jew on your face?