By Emily K. Alhadeff, Assistant Editor, JTNews

Celebrated Israeli writer David Grossman is on tour in the U.S. to talk about his latest novel, To the End of the Land, his first to deal with the matsav — the political and security situation — in Israel. After her son goes off to war, Ora decides to hike part of the Israel Trail, where she hopes no one will be able to find her when they come to notify her of her son’s certain death. Before finishing the novel, Grossman’s own son was killed during the final hours of the Lebanon War in 2006. Grossman says of this experience: “After we finished sitting shiva, I went back to the book. Most of it was already written. What changed, above all, was the echo of reality in which the final draft was written.”

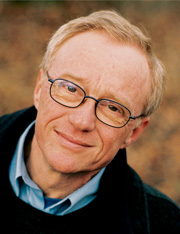

David Grossman spoke with JTNews about his life, his writing process, life and literature prior to his appearance last week at Town Hall.

JTNews: We know your own life and To the End of the Land overlap. But how did the idea for this story come about in the first place?

David Grossman: It’s very hard to trace the birth of an idea. Suddenly it is there. But I was looking for this idea for some years. I was looking for the way to write the story about the “situation” in Israel, but I was also trying to find a family story, the story of a family that will have to live within this situation and to show how the situation radiates itself into the life of the family.

My second son Uri was about to join the army, and a half-year before I finally got this idea of a woman who refuses to collaborate with the situation, to be herself and not function as a material of the situation. She decides that she will not sit at home and wait for the notifiers [the officials who would inform her of her son’s death] to come, she says, “to dig their notification into her.” By doing the most trivial act of not waiting for them she managed to reshuffle the whole situation.

JT: How much did you feel you were writing about your own life?

DG: I walked from the end of the land [from the northern border with Lebanon on the Israel Trail] to my home near Jerusalem. And when the book was finished I continued to walk in parts.

This was one of the sweetest experiences of writing this book: Being out, being in nature, being alone in nature, which is a special feeling. When you walk with another person you are more attuned to him or to her, and less to nature. When I walked alone, I became one more animal, one more creature.

I always like to know what I’m writing about. When I write about internal reality, I don’t have to leave my home for that. When I write about things that happen in the outer world, I like to take part in them. I remember when I wrote The Zigzag Kid I joined the detective unit for the Jerusalem police. When I wrote Someone to Run With I spent nights on the street. I love the way can integrate objective reality into subjective reality.

JT: Why did you choose a female character to tell this story? Was that a device you chose to use?

DG: I thought that a book that tells so much about family and raising a child, for me it was both natural and challenging.

I always feel in women — not in all of them — a slight skepticism regarding the big systems of our life, like governments, armies, war — all these systems that are created by men. They are regarded more by men, even though they kill them more. Men will sit at home and wait for the notifiers. It’s a woman who will refuse to take part in this automaton game.

JT: Why does Ora have the sense that her son won’t return?

DG: I think every parent in Israel…this is the most dominant feeling. The whole country lives in such fear for its own existence. The facts of death are so deeply formulated for us and engraved in our minds. There was almost no week or no day in Israel that someone has not died or been injured. The death of your beloved ones is so near to the surface.

JT: How is this story received in America and other countries outside of Israel? Do people have a hard time relating to such an Israeli experience?

DG: Everywhere I went, people said, “You wrote our story.” I’m coming here after a week in Scandinavia. They didn’t know war for 200 years. And yet, I think every individual feels his life is in a kind of danger. Everyone feels the fragility of his primal relationship to family, to friends. Everyone feels this doubleness. On the one hand, it’s a strong subcurrent of fear and anxiety. But the book is about life. Anyhow, the book is out here for a year now, so I really cannot complain about the way it was received here.

JT: To the End of the Land flows so naturally. Even in translation, the story just seems to spill out of your head onto the page. Explain your writing process. How was it compared to your other writing experiences?

DG: The writing process was no different than previous processes. I always write many versions. I have a vague idea, but I surrender to it. I write, then I get to a certain point and turn back. I never want to get to the ending. I want my book to surprise me. It was more difficult to organize this book because it has so many subplots, but I like it this way. It’s like a couple, between the writer and the book. Like a couple, you work together and change each other. This has really been the heart of my life.