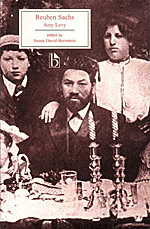

After Amy Levy’s suicide in 1888, Oscar Wilde wrote the following about her novel, Reuben Sachs: “Its directness, its uncompromising truth, its depth of feeling, and, above all, its absence of any single superfluous word, make it, in some sort, a classic.”

A classic, it seems, that very few outside the academic world have ever heard of.

Levy was part of London intellectual circles that included Wilde, Olive Schreiner and Eleanor Marx. she wrote forcefully about women’s issues; and she was the first Jewish student to attend Newnham College at Cambridge University.

So why have most people, especially those in the Jewish community, never heard of her, much less read her work?

According to University of Wisconsin Professor Susan David Bernstein, who edited new editions of two of Levy’s novels (Reuben Sachs and Romance of the Shop, released in 2006 by Broadview Press) there are a few possibilities.

One may be her suicide at the age of 27.

“She died young,” explained Bernstein, a professor of English, Women’s Studies and Jewish studies who specializes in 19th century British literature. “But she had a remarkable career.”

That career included short stories, poetry, magazine articles, essays and novels.

The other reason for her relative obscurity may be the unsettling nature of her work — most specifically Reuben Sachs.

Reuben Sachs centers on an extended Anglo-Jewish family in London, chronicling the fraught, quietly passionate relationship between Reuben Sachs and Judith Quixano, who, though not blood relatives, enjoy a “fiction of cousinship.”

Reuben is young, ambitious, and the “pride of his family;” it is therefore determined he must “marry money.” Judith is beautiful and Reuben adores her, but she is from the poorer, Sephardic side of the family, and thus the match is not considered suitable.

The novel is beautifully written and packed with sharp insights, especially concerning women’s choices, class prejudice, cultural appropriation, and, of course, what it meant to be both English and Jewish in late 19th-century London.

It is, however, passages such as the following that inspired (and still do inspire) extreme discomfort among many readers:

“He [Reuben] was, as I [narrator] have said, of middle height and slender build. He wore good clothes, but they could not disguise the fact that his figure was bad, and his movements awkward; unmistakably the figure and movements of a Jew.

“She [Judith] was one of the few people of her race who look well in a crowd or at a distance. The charms of person which a Jew or Jewess may possess are not usually such as will bear the test as being regarded as whole.”

It would be easy to throw the book down and conclude that Levy is re-enforcing nasty stereotypes in her own community. This, insists Bernstein, would be a mistake.

“People aren’t sure how to respond,” she explained. “This is a deeply ambivalent novel that explores multiple, conflicting identities.”

In Levy’s case, that meant having to grapple with being English, Jewish and female. She was, as Bernstein said, “part of, and not part, of the mainstream. She lived precariously across identities.”

The narrator of the novel, Bernstein noted, does not necessarily share the same viewpoint as its author.

“In Reuben Sachs, the narrator’s views seem to fluctuate,” Bernstein continued. “Sometimes the narrator seems to mimic anti-Semitic, offensive assumptions about Jews…. Sometimes the narrator seems to offer a critique of Jewish culture…. But sometimes the narrator seems quite sympathetic to the dilemmas of different characters who have been restrained by a secluded Jewish community in modern London, or who try to move beyond this community but meet with snubs.”

The challenge, she concludes, is how to interpret these varying perspectives and representations — a task that, in the end, is largely left up to the reader.

Being a writer and avid reader herself, Levy was very interested in the way Jews were being portrayed in the broader culture, specifically in novels written by non-Jews.

“There has been no serious attempt at serious treatment of the subject; at grappling in its entirety with the complex problem of Jewish life and Jewish character,” she wrote in her essay, “The Jew in Fiction,” which appeared in the London newspaper The Jewish Chronicle in 1886.

Up until that point, Bernstein explained, fiction tended to depict Jews as “faultless, pious, and good” — like Rebecca in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and most of the Jewish characters in George Elliot’s Daniel Deronda — or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, as villains.

Outside of fiction, Jews had been reduced to a “racial type” in articles and photographs by the likes of Robert Knox and Joseph Jacobs. Levy may have wanted to create something more nuanced and real, but the contemporary reviews of her novel were scathing.

The Jewish Chronicle did not even review the book, but the Jewish World wrote the following:

“[Levy] apparently delights in the task of persuading the general public that her own kith and kin are the most hideous types of vulgarity.”

The Academy, a non-Jewish publication, seemed to agree: “Miss Levy gives one the impression of having laid bare the failings of her people with a rather merciless hand, assuming, perhaps, by right of kinship a freedom of description which might be resented as “˜flat perjury’ if indulged by an unprivileged Gentile.”

Levy was born in South London in 1861, the second of seven children, to stockbroker Lewis Levy and his wife, Isabelle.

According to Bernstein’s introduction to Reuben Sachs, Levy had a “non-Jewish governess, an aunt who had a Christmas tree, and she was evidently familiar with both Hebrew and Christian texts.”

The family’s exact level of observance is not known, but they did belong to the Reform West London Synagogue of British Jews.

“Levy grew up in an assimilated family,” said Bernstein. “She was likely very familiar with the range of anti-Semitic and anti-Jewish attitudes circulating in her culture.”

Despite any obstacles her religion may have posed, Levy became the first Jewish student to enroll at Brighton High School, founded in 1871 by feminists Emily and Maria Shirreff. She was also the first Jewish student to enroll at Newnham College at Cambridge University.

“It’s very unusual that she had any university education,” said Bernstein, noting Levy’s double minority status as a Jewish woman. Women, she added, weren’t even granted degrees from Cambridge until 1948.

Levy’s keen intelligence and wit, however, revealed itself at early age.

When she was 17, she wrote a pointed letter to The Jewish Chronicle, refuting another reader’s insistence that “women have their sphere.”

“But I doubt if even the thought of becoming in time a favourable specimen of the genus “˜maiden-aunt’ would be sufficient to console many a restless, ambitious woman for the dreary performance of work for which she is quite unsuited, for the quenching of personal hopes for the development of her own intellect,” she wrote.

Throughout her career, Levy would continue to astutely examine the role of women in English society, especially in her poetry and in her novel Romance of the Shop, which focuses on four sisters who manage their own home and photography business in London.

In her two years at Cambridge, Levy studied classical and modern languages and also published her first book of poetry, Xantippe and Other Verse.

After she returned to her parents’ home in London, she continued to write poetry — as well as novels, essays, and short stories — and also traveled throughout Europe at frequent intervals. She was part of a vibrant intellectual and artistic community, and seemed to have the support of her family and a wide circle of friends.

She was at home, alone, and correcting the page proofs for her third collection of poetry when she committed suicide by charcoal asphyxiation on Sept. 10, 1888, at the age of 27.

There exist numerous theories as to what motivated her — one of the more popular being that she was a lesbian and suffered an unrequited love for the writer Vernon Lee (also known as Violet Paget). This, however, is pure speculation.

“We can’t really know,” said Bernstein. “She grew up in an all-girls environment and wrote passionate letters to many people.”

And according to Bernstein, we also can’t know why Levy chose to take her own life.

“We have no definitive answer or explanation for why Levy committed suicide, in part because the record of all her letters and notes is very incomplete,” she explained. “We do know that she engaged with the topic of “˜despairing melancholy’ [depression] and suicide in her poetry and in her short fiction.”

All the theories suggested by some scholars — including one that she was distraught over the criticism Reuben Sachs had received in the Jewish community — have been refuted by others.

Levy happened to be the first Jewish woman (in accordance with her wishes) to be cremated in England. A service was held in her memory at her family’s synagogue and her ashes were buried in Ball’s Point Cemetery in London.

“Her work,” wrote Oscar Wilde in his eulogy of Levy, “was not poured out lightly, but drawn drop-by-drop from the very depth of her own feeling. We may say of it that it was in truth her life’s blood.”

Negotiating identities