By Rabbi Seth Goldstein, Special to JTNews

One of my challenges as a rabbi is to make Judaism relevant across demographics. Part of the challenge comes from the fact that what necessitates how we teach Judaism to kids is different than how we teach Judaism to adults. And very often I find that people who study Judaism as adults are surprised by what they discover because they did not feel the Judaism they were taught as kids spoke to their adult sensibilities, and so were, for a time, turned off.

Well, of course. Judaism requires life-long study and engagement. What we learn as kids is not going to be the same as adults because what we need, what we understand, what we can grapple with is different as an adult than as a child.

This idea shouldn’t be foreign to our civic education as well since we are oftentimes stuck in a childhood vision of what our early American history and especially Thanksgiving is all about: stories of Pilgirms and Native Americans and a shared feast of mutual respect and understanding.

As adults, though, we know the story is much more nuanced and deeper than what we learn in elementary school. The history of the Native population in this country is a tragic one, complete with the ravages of colonialism, the forced exile, and the persistence of inequality.

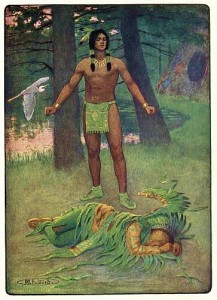

From The Story of Hiawatha, adapted from Longfellow by Winston Stokes and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Illustrator M. L. Kirk – 1910.

Every year, it seems, articles are published to remind us of this. While these articles are of course necessary, they remind me of something—that our education must extend beyond elementary school, and that meanings of events change over time. We tend to forget this. But we shouldn’t be surprised. When we are children we are told simple stories to acculturate us. As adults we are obligated to seek out the more nuanced truth behind these stories. Our mature minds require a mature understanding.

After sitting through our wonderful local Interfaith Thanksgiving Celebration this past Sunday, I was struck by the fact that Thanksgiving has a completely different meaning to me now that it did when I was younger. As a child, I was told the story of the Pilgrims and the Native Americans, sharing food in a spirit of fellowship. It was a historical celebration. As an adult, the themes of gratitude and the value of sharing dominate. It is a spiritual celebration.

The story of the “first Thanksgiving” is a myth in the classic understanding of the term—not an untrue story but a story that

is meant to convey deeper truths beyond particular events. Myths are not meant to write (or rewrite) history, they are meant to write the future. The mythic story of the Exodus from Egypt (soon to be a major motion picture—again) was not meant to tell the events as they happened, but to tell a paradigmatic story of redemption that is meant to shape our future.

The myth of the “first Thanksgiving” was one of unity and harmony across cultures. It was about an existing population welcoming a newly arriving one. It was about the promise of religious liberty in a new land. On the one hand, this covers up a tragic history. On the other hand, it embodies the ideals for which we hope and strive.

As with the story, so too with the celebration. The Passover seder is not meant to recreate an ancient Israelite meal of days gone by, but rather it is to serve as a symbolic feast of future redemption. That is why we find meaning in the meal, with the symbolic foods of bitterness and redemption not referring exclusively to the biblical story of Egyptian bondage, but to the places we recognize oppression in our own day.

When we sit down to the Thanksgiving meal, we would do well to do the same. The meal is not meant to recreate a historic meal that may or may not have happened. (Though one of the things I find powerful about Thanksgiving is that it is a seasonal celebration as well, and eating seasonal and native foods connects one to this land and time.) The meal is meant to be a time to reflect on where we find gratitude right now, but also where we are falling short as a nation in pursuit of those values of equality, liberty, mutual respect and pluralism.

And we are falling short. The struggles of our Native population persist. We are in a new national conversation about immigration—about who we are as Americans, about the extent of the American dream, and how we as a nation of immigrants treat those newly arrived at our borders.

And this week, with the failure of the grand jury in Ferguson, MO to hand down an indictment in the shooting death of an unarmed African-American youth, we are once again confronted by our national legacy of racism, white privilege, and institutional forms of oppression. The failure of our criminal justice system to even be open to the possibility of a trial rightfully inspires anger, fear, suspicion and disappointment.

We have much work to do.

As we mark this Thanksgiving, we do recall that story of the “first Thanksgiving”—but not as some pretty historical gloss. Rather, we recall it for what it really is: a story of promise and pain that contains within it both a devastating history and our highest ideals. Our job is to recognize the all of it, and by doing so, we will be able to transform ourselves and our communities.

Seth Goldstein is the rabbi of Temple Beth Hatfiloh in Olympia. This post originally appeared on his blog, rabbi360.wordpress.com.