Pomegranates have a special place in Jewish culture and history: they are reputed to have 613 seeds, which symbolizes the 613 mitzvot in the Torah. The Song of Solomon mentions pomegranate wine. Medieval Jewish mystics saw representation of the divine emanations of God in pomegranates such as that which dwelt upon the Sephiroth Tree, with both dark and light aspects.

But those are hardly Judaism’s first brushes with the tart red fruit. The love-hate relationship with the Punic apple goes all the way back to the Garden of Eden — at the time the Book of Genesis was being written down, apples were unknown in the Middle East, so many scholars believe the fruit on the Tree of Knowledge was actually a pomegranate — which would make the tree technically a bush.

Other cultures have also embraced the heavily seeded fruit as well. The fruit being full of seeds readily lends itself to be a symbol of fertility, bounty, and eternal life. Ancient Egyptians were buried with pomegranates in the hope of rebirth. The Hittite god of agriculture is said to have blessed followers with grapes, wheat, and pomegranates. At Chinese weddings, sugared pomegranate seeds were served to guests and pomegranates were thrown on the floor of the wedding chamber to ensure a fruitful union.

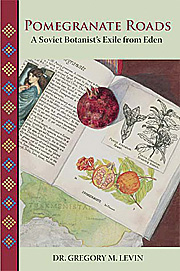

Barbara Baer is a font of information about the history, lore and modern varieties of pomegranates. But for an official pomegranate expert, we can look to Gregory M. Levin, a Jewish botanist who collected and studied wild pomegranates for a period of time in a distant corner of the Soviet Union. Baer is the editor and publisher of Levin’s Pomegranate Roads: a Soviet Botanist’s Exile from Eden. She spoke about the Levin’s pomegranates during a reading at Tree of Life Judaica & Books on Nov. 25.

Baer says her interest in Dr. Levin and his pomegranates stemmed from a chance encounter via her car radio in 2001. She was listening to “The World,” a public radio news program, when she heard travel correspondent Ann-Marie Reuff report from Turkmenistan in search of some of the last wild pomegranates on Earth. It was then that Baer heard the voice of Gregory Levin, speaking in Russian.

“Here [are] wild pomegranate forests, sheep and cattle are grazing on grasses, eroding land, harming young trees,” she recalls him saying in her introduction to his memoirs. The 1,117 varieties of pomegranates he had collected over nearly three decades and from four continents were dying of thirst in the parched climate. The post-Soviet government had cut off research funding and they lacked the money for even a pump to bring water up from the Sumbar River.

“We often carry water cans to each tree,” he had said.

Starting with what she had heard, Baer wrote an article for Orion Magazine about the pomegranate researcher in far Turkmenistan, and, at the magazine’s urging, she set out to find Dr. Levin, who by that time had moved from the former Soviet Union to Israel.

“Finally, I located him, thanks to the agricultural section of the Israeli Embassy in Washington,” says Baer. “Their agricultural section worked very hard to find him — he was a recent immigrant. After I found him, we corresponded.” Baer found his story compelling.

“[He was] a Jewish scientist who [had] experienced a lot of anti-Semitism and quotas against his entering various institutes,” she says. “He was able to become probably the world’s greatest pomegranate authority and had the biggest collection — in Turkmenistan in Central Asia — in the world.”

Baer says that for all the time and effort she has devoted to getting Levin’s story out and telling the world about his work with pomegranates, the two have never actually met. When she did locate him in Israel, Baer says she communicated with him mostly via computer. She says Levin used a computerized translating program to decipher her English and to render his Russian responses into a language she could understand. At other times, Margaret Hopstein, the translator of Levin’s book from the Russian and a longtime friend of Baer’s, served as their interpreter.

Owning a small press that she operates from her home town of Forestville, Calif., Baer says she decided that Levin’s story was one that could catch on with people, both for his personal history and because she knew, “not naïvely, that pomegranates are popular.”

Baer encouraged Levin to write his memoirs which, after translating and editing, she published as Pomegranate Roads (available from Floreant Press at www.floreantpress.com).

“My personal satisfaction is that being from about the same cultural background as Dr. Levin, I was able to preserve his voice,” says Hopstein. “He had many features of a Soviet intellectual who was prospering as a researcher only in voluntary exile in Turkmenistan. I understood his intellectual roots, his allusions.”

“Pomegranates are a seductive fruit, and they’re a Jewish fruit and they’re beautiful fruit,” says Baer, “and now they’ve become a health fruit.”

Rich in antioxidants and phytochemicals, a number of health claims have been attached to drinking pomegranate juice, from reducing the risks of prostate cancer and the onset of Alzheimer’s Disease to a daily dose to treat erectile dysfunction — a new twist on the old “apple-a-day” routine.

Chances are that the last pomegranate you ate, whether it was celebrating Rosh Hashanah or Thanksgiving, was wonderful. That is not to say it was sweet and flavorful, the seeds deep red and bursting with juice. The fact is, Baer says, virtually all of the cultivated pomegranates sold throughout the world are from a single variety: the Wonderful pomegranate. She says that people unfamiliar with the range of colors, from soft, pink seeds to sweet-sour ruby red varieties, have been missing out.

Before leaving Turkmenistan, Baer says Levin sent samples of the 60 varieties he considered most important to agricultural stations in Israel and at the University of California at Davis, near Sacramento, where the varietal fruits have been preserved and propagated.

“Davis took very good care of them, [and] propagated them heavily in a special plot where people can taste them,” she says. “Growers can get cuttings and propagate them and sell them to the public. There [are] still a lot of backyard gardeners, smaller growers who want to have the diversity of the pomegranate.”

Was Eve’s apple a pomegranate?