It would be easy to assume that Brother’s Shadow is a comedy — its two marquee stars, Judd Hirsch and Scott Cohen, are fine comedic actors and both have made their names in light-hearted TV roles.

Hirsch spent five years, from 1978 to 1983, playing Alex Reiger in the groundbreaking TV sitcom “Taxi” (which also introduced much of the world to Andy Kauffman, Carol Kane and Danny DeVito). Cohen, most recently spotted on the small screen as an assistant district attorney in the short-lived “Law and Order: Trial By Jury,” spent three years wooing and winning (and ultimately losing) Lauren Graham as Max Medina on “The Gilmore Girls.” Yet both actors also brought a sense of gravitas, at times bordering on tragedy to their parts — and it is that aspect of their work that is most in evidence in this small (by Hollywood standards) independent feature.

Cohen plays the central role of Jake Groden, the black sheep of his family and too often a victim of his own rebellious personality, desperately trying to stay on parole and off booze.

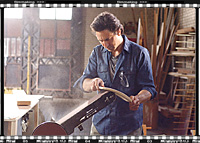

Hirsch plays his father, Leo, a proud and self-centered S.O.B. desperate to see the custom furniture shop he successfully built survive the death of his favorite son.

They are joined in this endeavor by Susan Floyd — a familiar face from a score of guest spots on popular TV dramas — as the widow of Jake’s identical twin brother Michael, and Elliot Korte as the couple’s teenage son, Adam.

Brother’s Shadow is the first feature film outing as a producer, director and screenwriter for Todd Yellin (who shared writing credits with fellow newbie Ivan Krim), and it bodes well for his future in cinema. This is a story with no explosions, no car crashes and no real villains, though all its heroes have their feet planted firmly in the clay. What it does have is a keen sense for the beauty of the streets of the Brooklyn neighborhood in which almost all the action takes place and a feeling for the irony endemic to people who have lost much, yet strive to hold onto some meaning in their lives.

There is also a deep appreciation for the art and craft of woodworking and the value of doing a job to the utmost of your ability. As filmed by cinematographer Kip Bogdahn, the fine grain and shiny finish of the wood is matched by the delicate colors and stately scenery of an old neighborhood that has held out in an era of urban gentrification and franchised sameness.

Ultimately it is a movie about last chances, gained and lost. Don’t go to see Brother’s Shadow expecting laughs but, by all means, go see it. While it leaves none of its characters living happily ever after, it leaves its audience with the idea that where there is life, there’s hope. And that may be the real essence of a happy ending.

Where there’s life, there’s hope