By Melody Amsel-Arieli, Special to JTNews

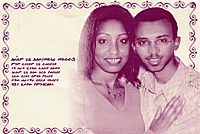

ShaSha and Gatchio chose wedding invitations featuring both hieroglyphic-like Amharic and Hebrew script. Their courtship, too, reflected a delicate balance between Israeli and Ethiopian traditions. Rather than meeting through a traditional arranged marriage, ShaSha and Gatchio met by chance, Israeli-style. But early on, bowing to custom, the couple sought approval of the religious leader of the Ethiopian-Israeli community, Kes Yosef.

Kes Yosef, a living treasure, has committed the genealogy of the entire Ethiopian Jewish community to memory, unto the seventh generation. After determining that ShaSha and Gatchio are “of good stock,” he searched for even the most remote familial relationship between them — a daunting task — as many Ethiopian families are intertwined many times over. Happily, he found that ShaSha and Gatchio, over the last 150 years, shared no common ancestors. Their wedding was on.

In the Ethiopian Highlands, weddings followed a traditional script: First, the families arranged their children’s union, agreeing on a bride-price, which might be either a herd of sheep or a considerable amount of money. Some four months before the happy event, the women of the village would begin to prepare the wedding feast from scratch, including enough beer, delicacies, and sweets for hundreds of expected guests. Finally, quantities of sheep were slaughtered for the feast.

On her wedding day, the bride, usually still in her teens, would be led, blindfolded, astride a horse to the ceremony. Only then, under the canopy itself, would her blindfold finally be removed, revealing, for the first time, her husband-to-be.

ShaSha and Gatchio, who have known each other for five years, married at a fashionable Beer Sheva “wedding garden,” in a canopy suspended over a romantic “lagoon.” In lieu of a horse and blindfold, ShaSha’s family sent her off in a flurry of pink rose petals. And after the ceremony, performed by an Orthodox rabbi, ShaSha and Gatchio braved a very modern “tunnel” of sizzling silver sparklers.

Some 600 guests attended, a modest turnout for Ethiopians, many of whose families are blessed with many children. While most of the men dressed informally, the women were in their full glory. Most of the older ones wore traditional white robes, their heads loosely draped with white gauzy scarves. Their only adornments, heavy gold earrings and pendants brought with them from Ethiopia, set off their fine features. Their Israeli-born daughters, on the other hand, chose bright turquoise, peach, or yellow confections, which complemented their dark complexions. And many “gilded the lily” by accenting their corn-rowed hairdos, or masses of black curls, with filigreed golden chains.

The musicians, Ethiopians all, tuned up nasally sounding stringed instruments called masenkos, and, to the beat of a decidedly Israeli synthesizer, swung into action. Despite the ear-splitting amplification — or perhaps because of it, their pounding rhythms lured guests onto the dance floor as surely as moths to a flame. Everyone massed around the bride and groom, forming loose circles, men facing men, women facing women, and began to dance. But there was nothing modern here, no hip-hop or rap. Except for an occasional flirtation with complex rhythmic patterns, like those popularized by the reggae crooner Bob Marley, the musicians stuck with traditional tunes. And the crowd responded enthusiastically, Ethiopian-style.

Shoulder-shimmying, probably adopted from Amharic tribes of old, features standing motionless while shaking the shoulders east-west, north-south, or to and fro, whichever way the music takes you. Putting reticence aside, even non-Ethiopians, responding to the beat and good cheer, jumped in and gave it a whirl.

ShaSha and Gatchio’s tale began centuries ago in the Ethiopian Highlands. Within their lifetime, it reached modern Israel, a continent and many light years away. Now, with their marriage, their tale will continue for generations to come.