(JTA)—In 1992, Edgar Bronfman was preparing to leave North America for Paris for his first meeting with then-French President Francois Mitterand at the Elysee Palace when at the last minute Bronfman decided he wanted to take an unexpected meeting in Geneva instead.

So he asked Serge Cwajgenbaum, Bronfman’s right-hand man in Europe, to phone the palace and ask to reschedule. The Elysee secretary, Hubert Vendrine, exploded.

“He asked me who Edgar Bronfman thinks he is to move around a meeting with the president,” Cwajgenbaum recalled. His answer? “The owner of half the wineries and vineyards in Bordeaux.”

In the end, Mitterand met earlier with Bronfman and then gave him a police escort to the airport so Bronfman could catch his plane to Geneva.

“It’s a good demonstration of the ease with which Bronfman conducted himself with world leaders,” Cwajgenbaum says.

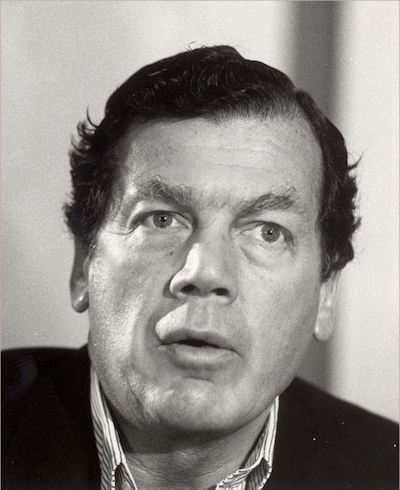

As the longtime head of the Seagram Company—at one point the largest distiller of alcoholic beverages in the world—Bronfman, who died last week at 84, was among the world’s most powerful industrialists, credited with expanding the company’s reach into the oil and chemical sectors and enhancing its reputation as a purveyor of high-quality spirits.

But Bronfman will be remembered in the Jewish world for bringing that same flair and jet-setter assertiveness to his defense of communal interests, most notably in his role as head of the World Jewish Congress, a position he assumed in 1981.

“Whether people liked him or disliked him, agreed or disagreed with him, there was a stature he had that no one has today,” said Rabbi Richard Marker, who served as executive vice president of the Samuel Bronfman Foundation in the 1990s.

In 1988, Bronfman flew in his private plane to Romania in the midst of an anti-Semitic campaign in state-run media targeting the country’s late chief rabbi, Moses Rosen. Shortly after landing in Bucharest, Bronfman was negotiating with the country’s Communist dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu, promising him better ties with the West in exchange for letting the WJC help Romanian Jews. He also warned that targeting Jews would increase Romania’s isolation and tighten the Soviet grip on Ceausescu.

There was another threat looming as well: The Romanian government’s plans to demolish ancient Jewish sites in Bucharest as part of a real-estate reform. Ceausescu was tried and executed the following year, but not before he managed to destroy several Jewish sites in the capital.

“If not for Bronfman’s intervention, he may have also destroyed the Choral Temple, Romania’s Grand Synagogue, during that critical period,” said Liviu Rotman, a Romanian historian who has studied Bronfman’s negotiations with Ceausescu.

The year before, in the wake of an Israeli media report that the Union of Swiss Banks had made a $40 million donation to the Swiss Red Cross as compensation for Jewish money pocketed during the Holocaust, Bronfman walked into the union’s Geneva offices and demanded to see the president. Bronfman came out of the meeting as he had come in: empty-handed.

“But that didn’t prevent him from bluffing and banging his fist on the table,” said Martin Stern, the British-born Jerusalemite and restitution campaigner who alerted Israeli media to the donation.

That encounter was only the opening shot in a much wider effort that culminated in the 1990s, when Swiss banks finally agreed to pay out roughly $1 billion in restitution.

The legacy of these and similar campaigns is evident at Bronfman’s office, located in the iconic Seagram’s building at 53rd street and Park Avenue in Manhattan, which is lined with photos of him with popes and presidents as well as a framed copy of Israel’s Declaration of Independence.

In the latter decades of his life, Bronfman would turn his attention more toward grooming the leaders of tomorrow than fighting battles on the world stage, particularly through his work with Hillel and the Bronfman Youth Fellowships.

Other projects he championed—some independently, others with a group of major donors informally known as the Study Group—include the Foundation for Jewish Camp, Birthright Israel, STAR: Synagogue Transformation and Renewal, the Partnership for Excellence in Jewish Education, and MyJewishLearning.com. Such efforts coincided with Bronfman’s own growing embrace of Jewish ritual practice.

“His involvement in Jewish things reflected a sense of, “˜If Judaism has all these interesting things to say, why didn’t I know more of it growing up?'” Marker said.

In the last weeks of his life, as his health faded, Bronfman’s love of learning continued unabated. The weekend before he died, he apparently finished Ari Shavit’s “My Promised Land” and had begun reading a book by Nietzsche.

Four weeks ago, after Bronfman’s appointments were canceled because he wasn’t well enough to come into the office, he called the executive director of his foundation, Dana Raucher, demanding to know why she cancelled his Talmud class. Raucher explained it was because he wasn’t coming into the office.

“What’s wrong with my apartment?” Bronfman responded.

“He loved the discourse, dialogue, debate and strong characters of the Talmud, how they were human and made mistakes, how they preserved the minority opinion,” Raucher told JTA.

Bronfman was also an advocate for women, gay Jews and the intermarried long before such views became the norm. He liked to relate how in the 1970s a Seagram’s human resource director had asked him to fire an employee because he was gay.

“He fired the HR director on the spot,” Raucher said. “He saw it as ethical, but also the right business decision. You fire people for what they do, not for who they are.”