By David Shayne, Special to JTNews

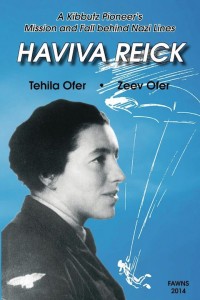

“Haviva Reick: A Kibbutz Pioneer’s Mission and Fall behind Nazi Lines” by Zeev and Tehila Ofer (FAWNS, $16).

Toward the end of World War II, the British and the Haganah (the underground army of pre-Israel Jewish Palestine) collaborated to train and insert some three dozen Jewish commandos into Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe. Their mission was two-fold: To try to rescue Jews and to aid the Allied forces, particularly airmen downed behind enemy lines.

A third were killed. Several were women, the most famous being the poet-soldier Hana Szenes, whom the Nazis captured and executed. Two weeks later the Nazis executed Haviva Reick, another female commando largely unknown outside of Israel.

“Haviva,” as the book is titled in its original Hebrew, is the subject of a detailed and fascinating biography by the husband-wife team of Tehila and Zeev Ofer. The Ofers are veterans of the Haganah’s elite Palmach unit and have their own compelling personal histories: Tehila came to Palestine after being caught on an “Aliya Bet,” an illegal immigrant ship, and interred in Cyprus, while Zeev had a distinguished career in the Palmach and then in the Israel Defense Forces. Now in their 80s, the Ofers remain actively involved in preserving the legacy of the Palmach.

Haviva was born in Slovakia 100 years ago, the youngest of five children, at the beginning of World War I. As a teenager, she became a Zionist, but rather than move straight away to Palestine, she remained in Slovakia to assist her single mother and lead Zionist youth until it was almost too late — she and two siblings managed to enter Palestine in late 1939 despite the British White Paper that severely restricted Jewish immigration, among the last Jews to safely reach Palestine from Europe just as the Nazi onslaught began.

But the rest of her family was soon trapped. Haviva, like others with family in Europe, followed events with an ever-growing fear and helplessness, which finally drove Haviva and her comrades to willingly return to the inferno from which they had escaped.

She spent the first four years living as a “halutza” a pioneer on a new kibbutz performing manual labor. In 1943, at age 29, she joined the Palmach, despite being considerably older than her comrades. Nonetheless, Haviva met every challenge and overcame the numerous hardships. She so impressed her younger male commanders that she herself was promoted to a field commander at first, and then selected for the British commando course, which led to her final mission and tragic end.

The Ofers capture her life and personality in great detail, as if they spent weeks interviewing Haviva in person. Despite never having met her, the Ofers bring much of Haviva’s sadly truncated life to light. Their book is not a two-dimensional paean to a fallen hero, but an intimate look at Haviva, the whole woman, including her faults and failures: Haviva was not always successful socially — she was nearly dishonorably discharged for unbecoming conduct — and had a rather tumultuous love-life, including a failed marriage.

Ultimately, Haviva was a force majeur, a woman of indomitable spirit and tremendous strength, a heroine in every sense of the word. Aside from telling this riveting story, the Ofers also provide wonderful insight into the lives of Jewish women pioneers and soldiers. It is an intense but fascinating read for any interested in Holocaust/World War II studies, life in pre-Israel Jewish Palestine, insight into the lives of female warriors, or just a good story about a great woman.