By Joel Magalnick, Editor, JTNews

The Seattle area is unique in that such a large Sephardic population settled here more than a century ago. While many of the families whose ancestors grew their families and fortunes here do their best to keep their culture and traditions alive, sometimes it’s best to let others do the heavy lifting.

“People are visual,” says Barri Rind, this year’s committee chair of the AJC Seattle Jewish Film Festival. “It’s very heartwarming for me to see that cinema celebrates these cultures and traditions that may disappear.”

Rind knows firsthand. As the Israeli-born daughter of Iranian Jewish immigrants, “we couldn’t always be openly Jewish,” she says. “When Israel was established, a lot of Jews had to leave Arab lands.”

Defining Sephardic Jewry isn’t always simple. The term translates as being of Spanish origin, with most of this area’s Jews coming from Turkey or the Greek island of Rhodes, where they migrated after their expulsion from Spain. Many more, who are also called Mizrachi Jews, hail from North Africa and Arab or Middle Eastern countries.

“To me, it doesn’t make any difference. Iranian, Iraqi, Moroccan,” Rind says. “We’re all connected in so many different ways.”

By focusing on Sephardic films in this year’s festival — a third of the screenings have Sephardic themes — Rind and festival director Pamela Lavitt both hope these artistic efforts not only give that population a taste of the old countries, so to speak, but also teach people whose only connection to the Jewish community might be through this festival.

“We can go deeper into our own roots and our own history, yet it has a broader appeal rather than a smaller appeal,” Lavitt says.

Though the majority of the Sephardic films — and the festival’s films in general this year — are features rather than documentaries, Iraq ‘n’ Roll and My Sweet Canary: The Story of Roza Eskenazi, The Queen of Rebetiko explore the musical history of Iraq and Israel’s Sephardic communities. An Echar lashon, an informal koffee klatch with Prof. Devin Naar, the Marsha and Jay Glazer Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Washington, will follow My Sweet Canary.

For Rind, however, it’s the opening night film that stole her heart, not to mention the hearts of the members of the festival’s film-selection committee. Mabul is the story of a teenage boy with autism who ends up back with his family after the institution in which he’s been living closes down from lack of funding.

“The family suddenly is faced with, How do we deal with this kid that needs 24-hour care?” said Rind, whose own 19-year-old son has a severe form of autism.

“It really hit home,” she says. “The way the movie is depicting how autism affects the family, the marriage, the siblings, [and] the community is very realistic and very authentic.”

In one scene, where after an especially difficult episode the boy’s mother sits down and cries, “I was that woman,” Rind says. “You don’t cry for yourself, you cry for “˜Where’s the solution? Who’s going to fight?’”

Rind has long been the one at the forefront of that fight. Mabul, she says, is powerful enough that she wants state legislators to attend to get a much greater understanding of her efforts over the past 15 years.

“It’s a great opportunity to teach the community what autism is all about,” she says.

Other films include this year’s offerings in the AJC Bridge series, which highlights the diplomatic mission of the American Jewish Committee. My So-Called Enemy premiered at last year’s Seattle International Film Festival and followed a group of Israelis and Palestinians who came together at a camp in the U.S. and tracked how their lives were affected over seven years.

The Judge is a documentary of the former chief justice of Israel’s Supreme Court, and will be followed by a debate and discussion. These films are the tip of the iceberg.

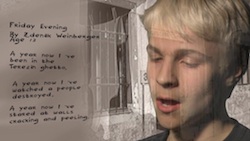

To close the festival, the committee decided to show something much closer to home. The Boys of Terezìn is a documentary from Seattle-based Music of Remembrance, an organization that unearths and commissions music related to the Holocaust. With former TV news reporter John Sharify as director and the Northwest Boychoir performing the music, the film documents the lives of 100 teenage boys in the Terezìn concentration camp who secretly created a magazine of their stories, drawings and poetry, and the reunion of four of the survivors 65 years later.

“It really is a gift to the festival to close on that note. We wanted to send it off with a true testament to life,” Lavitt says. “The fact that this film is premiering all over the country — it’s a little bit of Seattle exported, so we’re very proud.”