By Andy Bachman, Special to JTNews

“Folk song calls the native back to his roots and prepares him emotionally to dance, worship, work, fight, or make love in ways normal to his place.” Alan Lomax, Folk Songs of North America

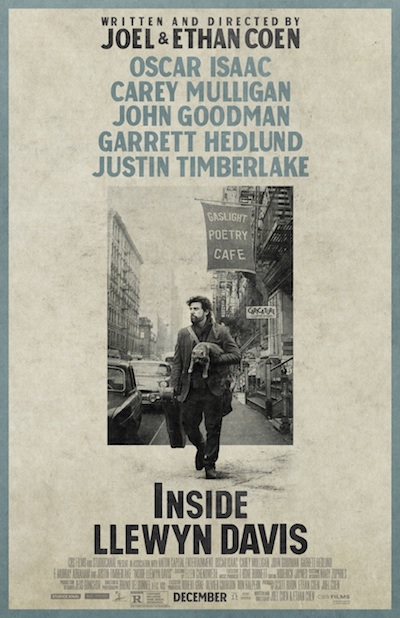

Over sushi in Brooklyn the other night, I was asked to justify why we made the kids see Inside Llewyn Davis, the Coen brothers’ spectacular new movie. The answers flowed easily. One: The creators of the film are geniuses and as far as art is concerned, kids, go with the geniuses. They always have something to say. Two: the movie is a snapshot of an historical moment in your hometown, New York. It’s important to know these things. An appreciation for the context of your life is important. And three (which took a bit more time to explain): There was once this guy named Alan Lomax, whose father John Lomax was the grandfather of the folk archival project for the Library of Congress and the WPA, who was a friend of your late great-aunt and who gave her a copy of his book which we have at home, one of a number of essential cataloging efforts that believe it or not changed the face of music history. There are Harry Smith’s recordings to talk about too, but the kids usually still complain when those go on.

The third, surprisingly, took no heavy lifting. For good measure we reviewed other facts about this rebel aunt: She stepped over her mother blocking the doorway to prevent her from going to college (UW-Madison in the 1930s, take a bow, please) and worked in DP camps for the JDC after the Holocaust before returning to a practice in New York.

So you see, folk song does call “the native back to his roots.”

Jews are about roots, of course. How could we not be? Meaning: Who are we without them? And yet the often derided roots (and the ignorance thereof) gives me great anxiety in our age. I suppose it helps explain why it is that for me, in a world of increasingly surface encounters, where the immediacy of experience and digitally rendered, character-limited responses (the idiot wind of discourse) which are prized over long-held beliefs and practices, I fear for the future.

We’re all so cosmopolitan, I know, I know. The grand melding that is taking place in our Digital Age has allowed for a greater confluence of cultural mixtures that pushes the boundaries of creativity to new heights, it’s true. Bieber has Hebrew tattoos and One Direction apparently “love” Jews. On balance, these are wins for our side. But not so much in a world where the tides are turning and leaving their marks on the shores of Jewish history: Too much distinction is a bad thing. Even Dave Van Ronk thought so: “We banded together for mutual support because we didn’t make as much noise as the other groups, and we hated them all — the Zionists, the summer camp kids, and the bluegrassers — every last, dead one of them. Of course, we hated a lot of people in those days.”

It was powerful to watch Llewyn Davis sing into the hurricane of popularizing forces that he knew he could never join; and it was downright energizing to hear a young Bob Dylan ascend at precisely the moment Llewyn Davis was getting his ass kicked by a prideful, defensive Southern man in a Greenwich Village back alley. History was being made, time moving forward, one soul crushed, another breaking through, cultural rebels commercial successes converging, diverging, and forging new paths on life’s journey.

It’s an old trope in America, this tension between roots authenticity and commercial success. And it applies to work in the Jewish community as well. Who we are. What we stand for. What we demand of ourselves and those in our community.

From literacy to ethically mandated behavior; from rite and ritual to the music and poetry of prayer; from what we eat to who we are and what we call home: Each are a manifestational limb emerging from the roots of Jewish history.

In a way, I was motivated to write this insignificant little blog as an homage to always remembering what matters. There’s a desperate scene in Llewyn Davis where the singer is stranded in a Chicago diner, his feet soaked and frozen, clinging to his bottomless cup of coffee, his only hope. I had days like that as a young man — feet frozen as a student in Madison, Jerusalem, or New York. Unsure of the future but dogged and determined to remain true.

I bet many of you can remember days like that. When you didn’t quite know how things would turn out but you knew you were a principled participant in a story larger, more expansive, and greater than yourself. Maybe a bud or blossom, at most a branch, on the many limbed project of your rooted existence.

Who knows? Maybe one’s life is like that branch, which for one brief moment, buoys the squirrel passing by, lifts his foot in a fleeting moment as an acorn falls, and after time, a new tree grows. Takes root.

We all do our part, don’t we?

So here’s to those with frozen feet and dreams to walk on dry land here or there, or, perhaps, on the Bonny Shoals of Herring.

I mean: What Jew doesn’t love herring?

Reprinted with permission from Andy Bachman, www.andybachman.com.