By Barbara Winkelman, Special to The Jewish Sound

Vivian Blum has a story to tell. It starts in Spain in the 900s, moves to Turkey in 1492, when the Jews were expelled from Spain, and lands in the United States in 1909, where it remains to this day. Soon there will be a chance for Vivian to look back and reclaim what was taken from her family: Spanish citizenship.

Currently, the Spanish government is working on legislation that will grant citizenship to those who can prove their “connections” to Sephardic Spain in 1492. It is intended to correct a “historic mistake” committed by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492 when they issued an edict expelling or converting all the Jews of Spain. The law’s passage is imminent, and may be approved as early as next month.

A person’s ties to Spain can be proven by one or more factors proving Sephardic ancestry, such as a family name, holiday and cooking traditions, and fluency in Ladino, the Sephardic language.

Vivian’s connection to Spain is through her mother’s family, the Chipruts, a well-known surname to Sephardic historians. Vivian speaks some Ladino, prepares Sephardic food, and belongs to Sephardic Bikur Holim. She and her cousins called their grandmother, Behora Kadun Louise Azose Chiprut, “Nona,” the Ladino term for grandmother. Behor Judah Chiprut, their grandfather, was “Papu.”

Outside looking in, Vivian’s Sephardic roots could not be clearer, but there is more than just a Sephardic bloodline that she inherited from her mother. There is the rich legacy handed down and changes from generation to generation. These make the bonds that enrich her family and keep it together.

“It all starts with our famous ancestor from the 10th century,” explains Vivian. “From generation to generation, all Chipruts are taught that they are descendants of Hasdai Ibn Shaprut, from Cordoba.”

Makes sense. The surnames are practically the same.

Hasdai Ibn Shaprut was the court physician and adviser to the caliph in Moorish Cordoba. He negotiated treaties with other kingdoms. Hasdai used his influence to improve conditions for Jews in Cordoba. Under his tutelage, Jewish culture thrived.

“Sephardic people are intense when it comes to tracing families,” says Vivian’s cousin, Louise Chiprut Berman, “simply in the way we name our kids — in a specific order: The first-born son is named after the father’s father, the first-born girl is named after the father’s mother, the second-born son after the mother’s father, and it goes down from there. You can trace our family through the names.”

“There are four Louises in the extended family,” continues Louise. “First there is Papu’s mother, whose name was Behora Kadun Louise Azose Chiprut. I also have two cousins with Louise in their names: Linda Louise and Lissa Louise,” as well as another, Louise Levy.

And then there’s the name Chiprut itself.

“My cousin Louise finds Chipruts all over the world,” says Vivian.

For example, Louise found a Joe Chiprut in Washington, D.C. through a Google search.

“We got to emailing back and forth,” Louise recalls. “He’s the same age as me. We exchanged family trees and the first names were all the same. We figured that we were probably related!”

Before the Internet, Louise wrote letters to Chipruts that she came across in newspapers and magazines.

“We’re all from the same sprout,” she says.

In 1492, Vivian’s ancestors migrated to Turkey, in the Ottoman Empire, where they stayed until the 1900s, when the Empire began to fall apart. Life in Turkey was tough for the Sephardic Jews.

Vivian’s mother, Esther Kahn Chiprut, describes her Nona and Papu’s jobs in Turkey: “My mother was a ‘domestic,’ cleaning wealthy homes from the age of 12 through 18, when she married my father, who was a longshoreman.”

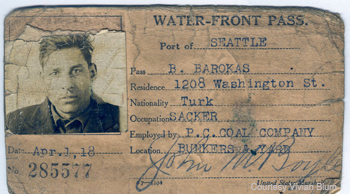

In 1909, Vivian’s Papu Behor emigrated from Tekirdag, Turkey, to New York, and then on to Seattle. Before Behor set sail, his cousin Sam Barokas offered to find him a job in the same Seattle coal mine where he worked. The catch was that Behor had to pose as Sam’s brother. When he arrived at Ellis Island, therefore, he told the immigration officials that his name was Behor Barokas.

Nona was not happy about that, and Behor eventually changed the family name back to Chiprut — after their first four children were born with the Barokas name.

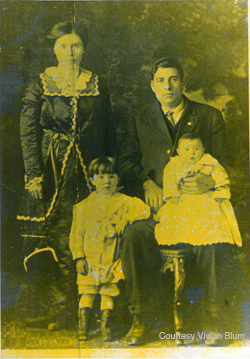

Two years after he arrived in New York, Behor sent for Behora. They settled in Seattle’s Central District, along with other Turkish Sephardim from Tekirdag,

The synagogue was the center of life for the Sephardim. The Turkish Sephardim moved within walking distance of Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation.

“It was a tight-knit community,” says Vivian.

“Everyone in the community knew each other,” adds Louise. “They took care of each other, they socialized together, they vacationed together.”

Sephardic Bikur Holim Congregation was incorporated in 1910. About 15 years later, Behor Chiprut became the first gabbai of the congregation, meaning he collected the funds for the synagogue and escorted people to the bima.

Behor had a strong, imposing presence. As gabbai, he took on the responsibility to ensure that proper decorum was upheld at all times.

Here’s a story that Vivian’s cousin, Judy Roberts Cohen, tells: “It was Yom Kippur and somebody had parked their brand new car in front of the synagogue. Papu had a friend, Asher Cohen, also a big guy, and they went out and picked up the car and moved it because it had no business being in front of the synagogue…. They knew who the car belonged to. He was a part of the congregation and knew that no one could drive on Yom Kippur. Papu was angry — he wanted to make a point.”

Vivian’s Uncle Joseph Chiprut confirms this story: “He was a strong guy!”

By 1914, the Chipruts had become deeply ensconced in their community. Behor held a steady job and they were settled in their new home. The stage was set for the next generation.

Next issue: How the Chiprut family today is preparing to return “home.”