By Emily K. Alhadeff, Associate Editor, JTNews

Who is a Jew?

This oft-pondered, never sufficiently answered question was the topic of a recent three-part class led by Rabbi Oren Hayon for Jconnectors at Hillel at the University of Washington this winter.

But this was no ordinary identity discussion group. Hayon was approached by 23andMe, a DNA testing company, which offered its Personal Genome Service test for $36, just more than a third of its standard $99. With a drop of saliva, 23andMe analyzes your DNA for ancestry and unique genetic markers. Around three dozen participants received DNA analysis, which can identify Jewish origins.

“I have been interested in how Jewish identity is constructed and maintained in Jewish young adults for a long time,” said Hayon. “That’s at the core of my work.”

Hayon turned to the Tanach, early rabbinic texts, and later commentators for insights into Jewish identity, especially on how it is bestowed upon Jews by choice.

While people come to Judaism on all kinds of personal and spiritual trajectories, rites like conversion — which requires immersion in mikvah waters — prioritize the physical body.

“There is clearly a sort of bodily component to Judaism,” said Hayon.

And now we can trace our Jewish identity right down to our DNA.

For geneticists, and for many Jews, that’s exciting.

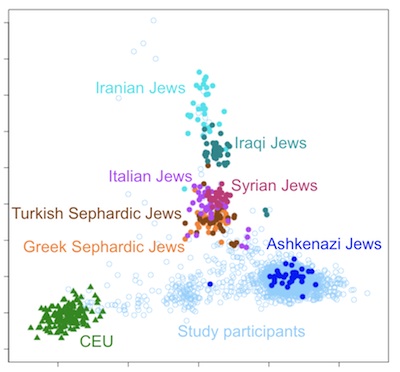

According to Catherine Afarian, spokesperson for 23andMe, the company reached out to the Reform movement’s Central Conference of American Rabbis, which is how Hayon found out about the opportunity. Geneticists are interested in Ashkenazi Jews in particular because the group is a fairly homogenous genetic sample and functions as a kind of control for studies. (European and Asian populations are sought for the same reason.) Furthermore, 23andMe hopes to learn more about genetic diseases and conditions that Ashkenazi Jews tend to carry, like Tay-Sachs, Crohn’s, and the BRCA breast cancer gene. While the FDA halted 23andMe’s health report service, which alerted customers about genetic issues that showed up in their results, Afarian says they are still collecting this data for research purposes but cannot market it until regulation is in place.

For the majority of Personal Genome Service test-takers, understanding who they are, genetically, is the most interesting thing.

Corinne Pascale, a Microsoft engineer and participant in the project, tested because she wanted to know more about her family.

“My mother was born Jewish, my father was not. He converted in. There’s a little bit of mystery surrounding him,” she said. Pascale had stories about both sides of her family, but no facts about who they were.

“There are all these really weird stories but there’s no paper trail,” she said. “As an engineer I’m enamored with numbers and concrete proof rather than stories.”

Pascale ended up locating her family’s specific origins and finding relatives no one knew existed.

“I think about myself now as link in a larger chain,” she said. “Now I see myself as this sum total of all these people. It’s 100 percent you, but now I realize how much of that 100 percent is other people.”

Pascale is far from the only one to be blown away by test results. Afarian, the 23andMe spokesperson, found out she was 50 percent Ashkenazi Jewish when she was 35.

Afarian’s parents had a one-night stand, and she never knew anything about her father, except that her mother thought he was Italian. It turns out he was Jewish.

“That was really informative because I was about to have my first child,” she said. “I’m still figuring out what it means to be Jewish.”

Since the first human genome was mapped in 2003 for $3 billion, technology and investments have brought the cost of send-away genome test kits down to just $99. Also bringing the cost down is the fact that the kits don’t sequence the entire genome, which is nearly identical for everyone, but just the variant part that traces the things that make us individuals.

Pascale was so affected by the test that she is building a website for Jewish genetic research. She’s basically picking up what 23andMe was forced to close, a service that informs Personal Genome Service customers about their risk for genetic diseases.

“If you look at the raw data you can actually draw your own conclusions,” she said.

With the help of her fiancé, Zach Stroum, Pascale is building a site, OyMyGenes.com, which is due to launch in April. OyMG, for short, will analyze results from 23andMe for the standard panel of Ashkenazi diseases.

“You are either at typical odds or you’re at increased risk,” she said. This is good information to have. But Pascale is very clear that this is not a replacement for professional medical consultation. She sees OyMG as a stopgap measure until 23andMe can resume its health reports.

“It’s a fun personal project that has a lot of meaning to me,” she said.

Lizzie Dorfman, a doctoral student in public health genetics at UW and a geneticist for 23andMe who helped Hayon facilitate the class, believes mapping our Jewish genomes may be a way to preserve history, particularly as we move away from events like the Holocaust.

“There’s a wide spectrum of how people identify as Jewish,” she said. Whether it’s matrilineal descent, or “dip and snip,” she said, “it offers a fruitful foundation for an interesting conversation.”

For Pascale, DNA is the link to family information lost between wars and the Holocaust.

“My genetic lineage is the paper trail. That data is all I have left of them right now,” she said. “These people lived and died and they loved and they got here…. I’ll never see their handwriting, but their stories are still being written.”