By Dmitriy Shapiro, JNS.org

Efforts to keep a significant collection of artifacts seized from Iraq’s Jewish community by Saddam Hussein from being returned to the Gulf nation by the United States may be picking up steam on Capitol Hill.

With just months to go before a June deadline mandates the return of the religious archive, U.S. Sens. Pat Toomey (R-PA), Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Chuck Schumer (D-NY) are shepherding a resolution that asks the State Department to renegotiate an earlier agreement reached with the Iraqi government. On Tuesday, the resolution passed unanimously in a voice vote in the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, and will now go to the Senate floor for a full vote that has not yet been scheduled.

“These priceless artifacts were stolen by the former government of Iraq,” Toomey, who introduced the bill on the Senate floor Jan. 16, said in a statement. “We should not ship the collection back to a country where their owners no longer reside.”

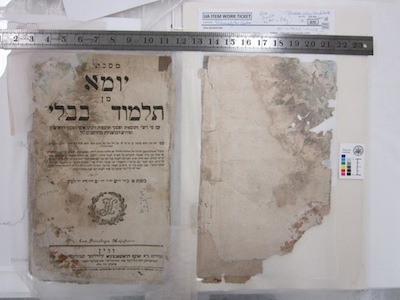

Comprising community records, Jewish books and sacred items belonging to the Baghdadi Jewish community, the archive was discovered on May 6, 2003, when the U.S. Army’s Mobile Exploitation Team Alpha raided the headquarters of the Mukhabarat, the Iraqi secret police. The building’s basement was flooded with around four feet of water, damaging many of the artifacts and kicking off a decade-long process by U.S. authorities to salvage and restore whatever they could. The effort cost U.S. taxpayers $3 million.

Keen to avoid appearing like the U.S. was looting Iraqi heritage, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration quickly signed an agreement with the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) administering Iraq at the time to return the collection.

Sen. Res. 333 currently has 17 co-sponsors from both parties. Besides Blumenthal, Schumer and Toomey, the original backers include U.S. Sens. Barbara Boxer (D-CA), Ben Cardin (D-MD), Tim Kaine (D-VA), Mark Kirk (R-IL), Robert Menendez (D-NJ), Pat Roberts (R-KS), and Marco Rubio (R-FL).

The legislative effort comes after years of outcry from the organized Jewish community in general, and in particular from Jews of Iraqi descent. Lobbying campaigns were run by the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, the American Jewish Committee, the Orthodox Union, and other groups.

“While the Hussein regime is no longer in power, these restored works documenting the Iraqi Jewish community rightfully belong to that community now living in diaspora around the world, not the oppressive country from which they fled,” Nathan Diament, executive director for public policy at the OU, said last week. “The Orthodox Union thanks Sens. Toomey and Blumenthal for their leadership and urges the Senate to pass this resolution in a timely manner.”

Those concerned with where the collection ends up are worried about whether they can trust the Iraqi government to care for the items—many of them fragile and historically significant—properly. Many fear that the original items will become inaccessible to the Jewish community.

Another argument is moral: Should the State Department return items to Iraq that were forcibly seized from fleeing Iraqi Jews or return them to their owners?

The resolution asks the State Department to reaffirm its “commitment to cultural property under international law” and its “commitment to ensuring justice for victims of ethnic and religious persecution.”

The long history of Jews in Iraq dates back to 720 B.C.E. According to estimates, as recently as 1940, Jews made up as much as a quarter of Baghdad’s population. But amidst rising Islamic nationalism and anti-Semitism during and after World War II, most Iraqi Jews fled the country, leaving much of their belongings behind or having it confiscated by authorities. Most of the remaining Jews left Iraq when the Ba’athist regime’s power and influence rose in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Today, almost all Iraqi Jews and their descendants live in the United States or Israel, and according to a State Department analysis in 2011, there are fewer than 10 Jews remaining in Baghdad.

Although a similar resolution has not yet been introduced in the House of Representatives, U.S. Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) signaled the possibility something would make it to the floor, although he believes a stronger stance than that in the Senate resolution is required.

“All these are very nice sentiments, but we shouldn’t negotiate with” the Iraqi government, Nadler told JNS.org. “We should just negotiate with the descendants of the Iraqi Jewish Community and to see what they want to do with it. It’s their property.”

According to Nadler, the CPA was essentially the agent of the United States, meaning that Washington essentially negotiated with itself; there is no agreement, therefore, with Iraq’s current government to break.

“Why should we negotiate with the government of Iraq at all?” asked Nadler. “I don’t see that they have any business in this.

“The CPA was the U.S. administering Iraq,” he continued. “It was headed by Paul Bremer, [who was] appointed by the president. Would we have negotiated with the West German government—Konrad Adenauer or Willy Brandt 20 years later—about the recovered Nazi loot that they stole from France, Russia or from the Jewish community? You return it to its owners if you can still identify them.”

Last November, Lukman Faily, the Iraqi ambassador to the U.S., told the Jewish Daily Forward that Iraq was committed to keeping the archive and that it should be viewed as a sign of a new, free Iraq welcoming all people.

“We appreciate where they are coming from, but you also have to appreciate this was an agreement, a legal agreement, agreed with the [CPA] back in 2003 and it’s owned by the Iraqi government,” stated Faily, who at the same time did not reject the possibility of negotiating another long-term loan.

Neither Faily nor the Iraqi Embassy responded to repeated requests for comment on more recent developments.

A State Department official, who was only authorized to speak anonymously, told JNS.org that while the U.S. was committed to fulfill its 2003 obligations, ongoing discussions between Washington and Baghdad are focused on finding “a creative approach to access and sharing of these documents and materials.”

“While the Department of State is not involved in issues of provenance regarding the [Iraqi Jewish Archive], we and the National Archives and Records Administration have regularly consulted with a variety of organizations within the Jewish community and others throughout this process,” the official said.

Meanwhile, the National Archives has organized 24 pieces from the collection into an exhibit, “Discovery and Recovery: Preserving Iraqi Jewish Heritage,” which is on display at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City until May 8. The same exhibit was displayed at the National Archives in Washington from Oct. 11 to Jan. 5.