By Joel Magalnick, Editor, The Jewish Sound

It’s almost inevitable when we travel, or have visitors come to town, that they will ask the same question: How many Jews are there in Seattle? The answer, we’ll find out later this year, is trivial, if not trivia. As both the sponsors and the conductors of a just-launched demographic study of the Puget Sound region’s Jewish community will tell you, it’s about the who, what, where and how we live our Jewish lives.

“We’ll get the numbers, because they’re important to have and to know where people are and to understand some trends,” said Keith Dvorchik, president and CEO of the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle, which commissioned the study, “but what we really are looking at are: What are the opportunities in the community? What are the needs in the community? What do people like, what do people not like? What are the attitudes about our community, and how can we adjust as a community to provide for these needs and take advantage of these opportunities?”

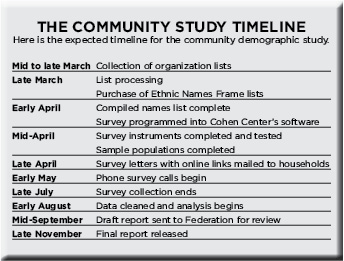

In late March, a team from the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University visited Seattle to explain the methodologies of the study and to begin collecting information from local Jewish agencies to begin formulating its questionnaire.

“There are certain things that every community wants to know about,” said Matthew Boxer, a research scientist for the Cohen Center who is overseeing the Seattle study. “As I like to say, there’s really only one Jewish community and everything is just a variation on the same in some ways.”

That said, “Seattle’s an interesting community — different in a lot of ways from a lot of communities we’ve studied in the past,” Boxer added. “We’re excited to have the opportunity to examine it more closely and get to know it better.”

The goal of the study, which is expected to be released around Thanksgiving, “is being done in the context of a very simple question, which is, ‘So what?’” Dvorchik said. “We want to make sure, and this is a Federation goal, that this study provides information that everybody can use for future planning.”

The goal of the study, which is expected to be released around Thanksgiving, “is being done in the context of a very simple question, which is, ‘So what?’” Dvorchik said. “We want to make sure, and this is a Federation goal, that this study provides information that everybody can use for future planning.”

As the Federation works to become the agency that every other Jewish organization looks to for building partnerships and taking a high-level view of the community as a whole, Dvorchik said he hopes the survey “will provide information that will allow agencies to say, ‘Wow, there’s this need here that we didn’t know of, or the need here is less than we thought so maybe we’ll spend more of our resources somewhere else.”

Boxer said the study will do just that.

“We can compare interfaith families to endogamous families where both partners are Jewish,” he said. “We can compare people in different age ranges…. We can compare households with children to households that don’t have children.”

Getting even deeper, as Boxer’s team reaches out to local households with its questions, they want to find out how this community lives its Jewish lives.

“There’s a substantial proportion of the population for whom Judaism is not at all a religion. It’s their background, it’s their heritage, but they don’t practice it as a religion,” Boxer said. “They are nevertheless very proud to be Jews and they do all kinds of Jewish religious things.”

That aspect of the study excites Judy Neuman, CEO of the Stroum Jewish Community Center.

Given that the demographic data the SJCC and other agencies work from is 14 years old, “getting some of that factual demographic information will set a new baseline,” Neuman said. “We really do want to understand all kinds of things, from what would it take to get a Northender to drive across the bridge [to Mercer Island]? What kind of programming will really move them?”

Though Boxer said the survey won’t put too much effort into finding the Jews who don’t want to be found, Neuman believes it will give a holistic view of what the Jewish community looks like.

“The more we can have some good information, the more we can have that flexibility to serve [our members’] interests,” she said. “It will move our programming forward probably in different directions. Not unilaterally, but in a direction we’re not even thinking about today.”

Will Berkovitz, CEO of Jewish Family Service, said he is curious about how the demographics of the Seattle area’s Jewish community are changing.

“For me, I think it helps us define the needs of our population and who our population is, and give clarity on what they want and need,” Berkovitz said.

In building the survey’s questions, it’s a delicate process to balance input from so many organizations that want data specific to their missions with a list that doesn’t overwhelm the respondents.

“We try to leave everybody equally disappointed, and try to give them as much as possible of what they really need to be able to do what they want to do,” Boxer said.

The methods for finding and surveying the community are far different than they were in 2000, the last time the Federation led such a study. With the proliferation of cell phones, opening a phone book and calling names that look Jewish doesn’t work if people don’t change their numbers when they move into or out of town — if they even appear in the white pages at all. Instead, the center is using what Boxer said “gets you the vast majority of the Jewish population for the most affordable cost.”

That starts with the list. During March, the Cohen Center collected contact lists from every Jewish organization and synagogue in King, Pierce, Snohomish and Kitsap counties, with the promise that these lists would be used solely for the survey, then destroyed.

“It’s not just the Federation, it’s not just the JCC or the synagogues, it’s cultural groups, it’s social groups, it’s secular groups, college groups, groups for singles, groups for elderly, groups for people in need, whatever’s out there,” Boxer said.

Each household, depending upon its source, is then assigned to a layer, such as synagogue member, day school family, or senior citizen. Boxer’s team then weights each layer based upon priorities the community has set. That weight then determines the sample size for each layer. In the final analysis, any under- or oversampled layers will use those weights to ensure an accurate view of the community as a whole.

The survey questions will be based on the same priorities.

Second, the surveyors will use what’s called the ethnic names frame, five lists purchased from data brokers that contain surnames of people who disproportionately identify as Jewish. One of those lists specifically targets Sephardic names, which Boxer said has been a common concern in Seattle. He said he has also heard that a small Persian Jewish community exists in the area, so he may need to compile a list encompassing that group as well.

“It’s worth looking into in the offhand chance that there are a thousand [Persian] Jews,” he said. “It’s not a lot, but it’s a population.”

The Federation spent more than a year preparing to launch this community study, the cost of which will not exceed $149,900 plus expenses, budgeted over five years.

“We will continue to reserve the dollars after that to ensure we have money to refresh the data or update the study at appropriate intervals,” according to Dvorchik.

While the Cohen Center is not the only organization that does such work, Dvorchik said the committee overseeing the study felt the center’s methods would get the best results given limited funds.

“The Cohen Center made everybody feel the most comfortable that we would get the most results that we wanted, not in terms of specific numbers, [but] that they would be able to answer our questions, that it would be a scientifically valid study,” he said.

Citing studies in New York and Portland by other demographers that turned out to be highly skewed, “there’s a very comforting feeling using them that we’re going to get real data in a form that will allow us to use it,” Dvorchik said.