By Joel Magalnick, Editor, The Jewish Sound

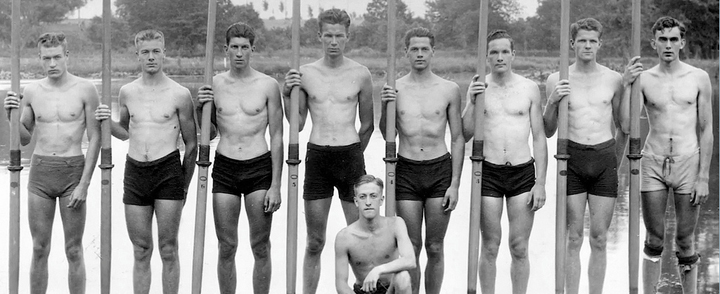

For those of us that live in or grew up in Seattle, “The Boys in the Boat” (Viking Penguin, paper) is even more special than the tens of thousands of readers that last year made this book a silent bestseller, inspiring its paperback release earlier this summer. That we know what happens in the end — the spoiler alert is printed right there on the cover, after all — is beside the point. This is a hometown story, and Daniel James Brown’s telling of the nine University of Washington men, who came from vastly different backgrounds to beat the heavily favored German Olympic rowing team in Berlin in 1936, more than does the story justice.

The bulk of the story is told from the perspective of Joe Rantz, a poor country boy abandoned by his family and left to his own devices to make a life for himself. By the time Joe eventually got admitted into the UW, he’d lost his mother and been forced out of his home by his father’s new wife to fend for himself. Rantz was better educated about the harsh world than most other kids his age ever should have been, but he stayed in school and survived on his own devices. Given how he spent his teen years chopping wood after finishing his daily schoolwork, and as his legendary coaches on the UW rowing team quickly learned, he had what it took to be a world-class rower.

The bulk of the story is told from the perspective of Joe Rantz, a poor country boy abandoned by his family and left to his own devices to make a life for himself. By the time Joe eventually got admitted into the UW, he’d lost his mother and been forced out of his home by his father’s new wife to fend for himself. Rantz was better educated about the harsh world than most other kids his age ever should have been, but he stayed in school and survived on his own devices. Given how he spent his teen years chopping wood after finishing his daily schoolwork, and as his legendary coaches on the UW rowing team quickly learned, he had what it took to be a world-class rower.

Brown takes us through Rantz’s life — mostly because he was one of the last surviving members of the Olympic team by the time the story fell into the author’s lap — but sometimes at the expense of the others’. As the team trained in Lake Washington’s cold, choppy waters, the world was in the throes of the Great Depression and the war drum had begun to beat in Europe. Brown deftly juxtaposes the budding rowers’ training amid blistered hands, biting rainstorms, and their growing popularity with Hitler’s rise, the deepening restrictions of Nazi rule, and the continued discrimination against its Jewish population.

Because I read this book from a Jewish perspective, I noted a few interesting inconsistencies from what I’ve learned of that time: One, Brown makes the oft-repeated mistake that people on this side of the Atlantic were unaware of Europe’s murderous slide into darkness, and therefore remained silent. But even looking through copies of this very newspaper from that time would show how wrong he was. Two, as the UW Olympic team prepared to embark on its trip to Germany, coxswain Bobby Moch’s father dropped a bombshell: Their family was Jewish, despite the elder Moch’s painstaking attempts to hide their background in their adopted Washington State — and they still had family in their native Germany. But we learn nothing about whether Bobby sought his family out, whether they survived the Holocaust, or how Bobby felt after his team eked out victory for the Olympic gold. That could have made for an even more dramatic literary finish.

And finally, as these men — along with the rest of their fellow Olympians — are taking in the (heavily whitewashed) sites of Nazi Germany, Brown uses a Jewish family in the Olympic village as an example of what happened to these regular folks after the games ended. Perhaps for readers who are less knowledgeable about the Holocaust, it could have provided insight, but the effort felt overdone and like it came out of nowhere.

But those are small quibbles for a book where in our mind’s eye we can take our place on the shores of Lake Washington to watch these champion rowers at a time when rowing was the sport to watch, to see the neighborhoods as they looked then — which aren’t so different from today — that slope down into Portage Bay, and the old, rickety boathouse at the end of the Montlake Cut where the boys turned into men. That we could feel each splash and each muscle’s ripple in these rowers’ rhythm is what separates “The Boys in the Boat” from an afternoon canoe ride through the Arboretum.