By Janis Siegel, Jewish Sound Correspondent

The United States has little to worry about when it comes to the possibility of an Ebola virus outbreak here, according to Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Ebola researcher Dr. Leslie Lobel: It’s not airborne, it requires direct contact with an infected human or animal, and the U.S. health care system has decades of experience successfully treating individuals who’ve returned from far-flung locations with similar infections.

But what keeps Lobel returning to Africa at least four times a year is his research testing the blood of nearly 120 people who were infected with the Ebola virus but either survived or didn’t get sick. Their blood seems to mount a strong defense that protects them from succumbing to the disease.

“We’re looking for those people who have the best antibodies to neutralize the virus,” Lobel told The Jewish Sound. “We identified those survivors with the best immunity, taking the antibodies from their blood and then producing them so that they could hopefully be used as a therapeutic for future outbreaks of Sudan Ebola virus.”

Lobel received $1.2 million of a $28 million, five-year National Institutes of Health grant awarded to a consortium of scientists to create a center dedicated to finding a serum to fight against two hemorrhagic fever viruses, including Ebola. The grant will help Lobel isolate those antibodies while his team reproduces them for testing in animals.

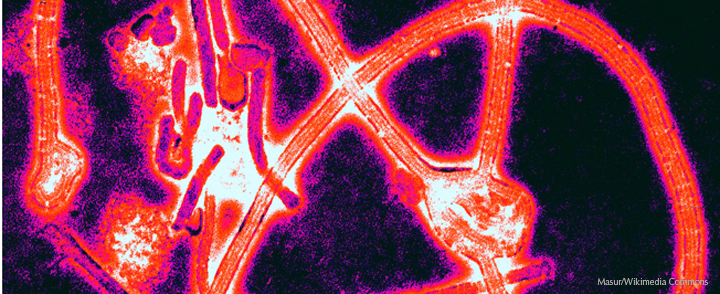

Scientists have identified five stable strains of Ebola. Reston is not lethal to humans, said Lobel, and Tai Forest is so rare a strain that no one is very concerned with it. The other three are the Sudan, Bundibugyo, and the Zaire.

“The current outbreak is the strain that’s known as Zaire,” said Lobel. “That’s historically been the most lethal although the case fatality rate of this current outbreak is not as bad as the original outbreak of Zaire — probably about 60 percent.”

Lobel has been working with two Ebola strains and a related hemorrhagic virus, Marburg Virus, since 2002.

In Lobel’s other study, his team has been collecting blood samples from survivors who have maintained their immunity over time. Every few months, Lobel and his group take white blood cells from survivors’ blood samples, and identify those that produce the antibodies that are strongest at neutralizing the virus.

“It’s unlikely that people have different barriers to infection because viruses get into your mucous membrane and cuts in your skin,” said Lobel. “It’s a matter of the differences of the genetic makeup of a person that probably gives somebody a better capability of surviving. People’s immune responses are very different.”

Lobel’s best guess, so far, is that an infected person who gets sick has an immune system that just doesn’t make the right combination of antibodies to fend off the virus. But the precise factor in the survivor’s blood is still unknown.

“The one thing we do know,” said Lobel, “is that people who don’t survive have a disregulated immune response — it’s not producing the right combination of molecules to give an appropriate response.”

Outbreaks of the Ebola virus, however, play a relatively small role in the spread of disease in the general population all across Africa, according to Lobel.

The more urgent health threats are infectious diseases like dysentery, cholera, childhood diseases, and plague as well as widespread crop failures and animal diseases, which he also researches.

“The animal diseases are the biggest problem in Africa and nobody talks about it because it doesn’t affect people,” Lobel said. “But interestingly, if affects people in a much larger way than Ebola.”

Lobel cited malnourishment as an obvious effect, but also security concerns.

“When people don’t have enough food, it leads to a lot of unrest,” he said.

Researchers do know that outbreaks of other diseases, such as measles, are worse in the developing world, said Lobel, and that nutrition and general health do play a part in the ability to fight off diseases. But he is also clear that it’s not the determinative factor.

“It may make a small dent,” said Lobel, “but it’s not going to make the difference between no people dying and 50 percent of the people dying. It’s not a strong or weak immune system — it’s the right response that counts.”