By Joel Magalnick, Editor, JTNews

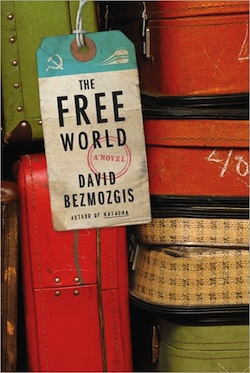

A funny thing happened while I was reading David Bezmozgis’s new novel The Free World (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, $26). I went out for beers with a few folks and it came up that one of the women in our party had emigrated from the Soviet Union when she was a little girl. When someone asked about her experience, I told the story. That is, I told the story through the eyes of Alec Krasnansky and his extended family, who left Riga, Latvia in 1978 to make their way to Chicago.

I noted the crowded immigration centers, the months spent in Rome (“Ladispoli,” my friend corrected me, not realizing that the town was essentially a seaside suburb) where the influx of Russian Jews hustled and whiled away the days as they awaited their visas to enter their new promised land. With my friend’s story I got it pretty much right.

With Alec, so did Bezmozgis.

When the Soviets opened the doors for Jews to leave in various waves in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, we would hear the same story over and over as these new Jews entered the United States and Israel. Life was difficult. People waited in long lines for just a loaf of bread. The KGB watched their every move.

Yet Alec’s life wasn’t so terrible. Yes, they had to watch their step. And when Alec and his brother Karl made the decision that they wanted to leave — based more on curiosity and profit than on oppression — things got difficult for their father, Samuil.

Both had second thoughts about submitting the application. Karl had managed to acquire a large apartment in a just-completed building and was waiting for the decorator — they had decorators under Soviet rule? — to help them pick out wallpaper before his wife would move in. Alec had just impregnated his beautiful but married girlfriend Polina, his coworker in the radio factory.

Everyone in this story has baggage, and not just the Russian knickknacks they drag with them across Europe to sell in Rome’s open market.

Polina had made top marks in school to achieve her position at the factory. Yet despite her intelligence and looks, she allows herself to be led by whichever man will pay attention to her, whatever the consequences. She divorces her first husband (whom she had agreed to marry only because she had terminated their pregnancy and thought it was the right thing to do). She accepts Alec’s proposals of marriage and America, despite the toll it takes on her aging parents, because again it feels like the right thing to do.

Samuil, it turns out, leaves his motherland under duress. This old (though only in his early 60s), cantankerous survivor of pogroms and several wars had seen his mother and brother killed. He had worked his way up to a high position the Communist party. He had a car and driver and a willingness to die rather than of be subjected to the excesses of the outside world. He lost everything as soon as Alec and Karl put in for their exit papers. You know things won’t go well for him when the border agent sweeps his medals — which give him more pride than his good-for-nothing sons — into the garbage.

The Free World shifts gracefully between past and present, going as far back as Samuil’s childhood in pre-Revolution Russia and as recently as the weeks leading up to the Krasnansky clan’s humiliating border crossing. While the past offers context and depth, the story shines in the present: The stuffy offices of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the faceless bureaucracy of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the apartment Alec and Polina share with their one true friend, a stateless tour guide.

These Jews are not the poor, huddled masses many of us may remember at the height of the Russian Jewish movement of the late ‘70s. These Jews are angry. They’re shrewd. They’ll bust your lip if you try to go too far with their sister. At least that’s what happened to Alec. But they’re also apprehensive — frightened even.

In the auto garage that Karl somehow owns, which might be a front for illegal activities —who knows what he’s doing with those heavily tattooed former Russian prisoners? — Alec finally gets it: These tough guys are just as scared as everyone else about what awaits them in this brave new world.

Like life itself, nothing ever goes as planned, as the Krasnansky family finds out when their sponsor in Chicago changes her mind and they must decide where they can go. Boston? San Francisco? Calgary?

“To live in these places you could marvel at them every day, but who did? In the same way you took a beautiful girl and made her into a wife. The wife remained enchanting, full of mystery, to everyone else.”

For 350 pages Bezmozgis keeps us enchanted, interested, and waiting to see what mystery the family must solve to get them to their new, freer world.