By Joel Magalnick, Editor, The Jewish Sound

By any stretch of the imagination, the Jewish community of the greater Seattle area is a growing, vibrant place. Where those Jews are and how they live offers a fascinating and at times surprising overview of who we are as a community. According to the 2014 Greater Seattle Jewish Community Study, a demographic report commissioned by the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle and conducted by the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University, which was released in late January, that growth clocks in at about 70 percent since the last study was conducted in 2001.

These statistics are based on a sample size of 3,058. In comparison, the 2013 Pew Research Center’s Survey of American Jews had a sample size of 3,475.

“We have almost the same number just for Seattle as Pew did for the whole country,” said Keith Dvorchik, president and CEO of the Jewish Federation. “It’s a very, very robust data set and it allows us to dig deeper than we’d be able to do.”

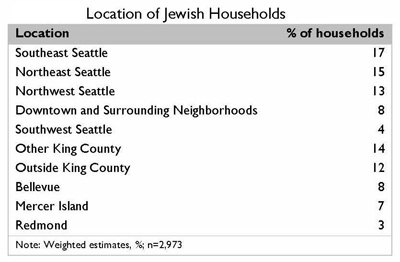

The number of Jews who live in the five counties around Seattle — King, Pierce, Snohomish, Island and Kitsap — comprise roughly 63,400 Jews in 33,700 households. King County by far has the largest concentration in the region, at 85 percent. That’s not a big surprise, but where in the county they are was.

“I don’t think we expected to find quite such a high proportion of the community living in the City of Seattle itself,” said Matthew Boxer, a research scientist at the Cohen Center who led the study, via email. “I think we expected to find a greater share of the population in Bellevue, Mercer Island, Redmond, and some of the other suburbs.”

“I don’t think we expected to find quite such a high proportion of the community living in the City of Seattle itself,” said Matthew Boxer, a research scientist at the Cohen Center who led the study, via email. “I think we expected to find a greater share of the population in Bellevue, Mercer Island, Redmond, and some of the other suburbs.”

But the large presence of Jews in Northwest Seattle — neighborhoods north of the Ship Canal such as Ballard and Greenwood — surprised researchers.

“The growth in Northwest Seattle has been dramatic,” Dvorchik said.

The only easily accessible Jewish organization to that area is the Queen Anne-based Kavana Cooperative. Though Northeast Seattle — the University District, Wedgwood, Ravenna — offers multiple synagogues and the Stroum Jewish Community Center preschool, among other services, “if you live in Northwest Seattle, 30 minutes may or may not get you to the synagogues in Northeast Seattle,” Dvorchik said. “It’s clear that there’s a big challenge.”

And, perhaps, opportunity.

“I think we’re going to have to meet people where they are and move to more of a neighborhood structure,” said Judy Neuman, CEO of the Stroum JCC, of these findings. “I think it’s more about breaking programs up and making them more intimate in size where we can and going out into the community.”

Will Berkovitz, CEO of Jewish Family Service, said his agency’s mission is moving in the same direction where the agency’s outreach aims for engagement “not in a purely religious context, but in a context where it reaches them where they’re at,” he said. “I feel quite optimistic with what our strategy is. It’s lined up really nicely with what the study enforces.”

Given how the community has grown and moved in just the past 15 years — as well as the data point that we are unwilling to drive more than 30 minutes to get to a program — building new structures is probably not the right solution to this issue.

“The population will shift,” Neuman said.

“The population will shift,” Neuman said.

And while the community is wealthy — 54 percent have annual household incomes above $100,000 — 7 percent of us range between “just getting along” and living in poverty.

Berkovitz called that “a pretty big number,” though he cautioned that JFS’s programs that address addiction, mental health and domestic violence transcend income levels.

Then there was the biggest surprise of all: The level of education.

“We’re talking about a highly educated, highly knowledgeable community that values education and everything that goes along with education,” Dvorchik said. “Twenty-six percent of

Americans have a college degree. According to Pew, 58 percent of Jewish Americans have a college degree. The statistics show that white Seattle, in the five-county area, 58 percent have a college degree, and in the Jewish community in Seattle, it’s 89 percent.”

In addition, 55 percent have a master’s degree or higher, double the average of Jews nationwide. People working in tech and the sciences make up about 14 percent of occupations, and 12 percent work in some type of management, which likely accounts for those high education numbers.

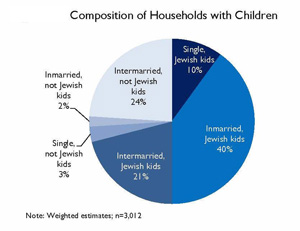

It probably comes as no surprise to many of us that Seattle has a higher rate of intermarriage than the rest of the country: About 56 percent of Jews are intermarried, 12 percent higher than the national average. However, of those families 44 percent raise their children Jewish while 40 percent raise them with no religion or haven’t made a decision.

It probably comes as no surprise to many of us that Seattle has a higher rate of intermarriage than the rest of the country: About 56 percent of Jews are intermarried, 12 percent higher than the national average. However, of those families 44 percent raise their children Jewish while 40 percent raise them with no religion or haven’t made a decision.

“Seattle reflects national trends in that about half the children in intermarried families are being raised Jewish in some way, but very few are being raised exclusively in another religion,” Boxer, of the Cohen Center, told the Jewish Sound. “That points to a tremendous opportunity for the Greater Seattle Jewish community, and also a great challenge.”

That challenge, Boxer said, comes in programming for interfaith families to make them feel comfortable.

“Previous research shows that children of intermarriage tend to identify as Jews as adults if they were exposed to high quality Jewish educational programming as children,” he said.

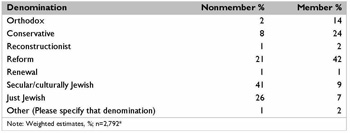

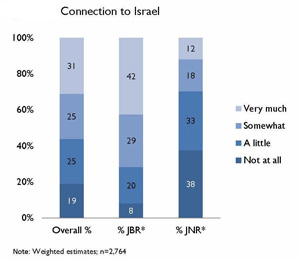

The survey divided the population between those who identified as being Jewish by religion and those as being Jewish not by religion — people who consider themselves Jewish, but perhaps more culturally. When those numbers are broken out, the ratio is about 2 to 1 for all age ranges — a surprise only in that it matches the same rate as young adults nationwide. Far fewer Jews here identify as Jewish by religion in the higher age ranges than nationally.

And then there’s this odd bit of data, which the Cohen Center had to triple check to make sure they actually had it right: While the region has a higher level of synagogue membership than the national average, the level of participation is much lower.

“It’s a weird dynamic that you wouldn’t expect,” Dvorchik said. But he attributed that enigma to the high level of philanthropy the survey revealed.

“Even though we aren’t going to attend, there are other people who will so we need to help support the community,” he surmised.

And though the majority of those philanthropic dollars and volunteer hours went outside of the Jewish community — 48 percent don’t volunteer with any Jewish organizations — comments from respondents made it clear that it was their Jewish values that inspired giving.

JFS for one sees opportunity is in volunteerism, in particular those who the agency can “engage these folks who are really on the margins [and] give them an opportunity to pass on their Jewish values,” Berkovitz said. “JFS is in a very unique position in this community to help be a gateway into the broader community.”

Boxer said the complexity of the data made this study as complicated as any the center has done. He sees obvious highlights as the community’s growth, which he expects to continue growing over the next decade; high involvement in a wide array of activities both inside and outside of the Jewish community; its affluence and high emphasis on education; and that this community “is deeply invested in and committed to social justice, both in the Jewish world and more universally,” he said.

Boxer said the complexity of the data made this study as complicated as any the center has done. He sees obvious highlights as the community’s growth, which he expects to continue growing over the next decade; high involvement in a wide array of activities both inside and outside of the Jewish community; its affluence and high emphasis on education; and that this community “is deeply invested in and committed to social justice, both in the Jewish world and more universally,” he said.

With the study now in hand, it is up to the Federation to figure out how to make use of the data in a way that facilitates community growth.

“We need to be doing deeper dives to understand some of the reasons behind the information that’s in here so we can better address it,” Dvorchik said.

Neuman hopes community organizations strike now, while the iron is hot, to work together to start taking action on using this data intelligently.

“I don’t want two months to slip by and have it end up on the bookshelf. Nor do I want each organization to look at it myopically within their own lens,” she said. We need to “look at it as a collective community.”

As such, the Federation will be hosting town hall meetings about the study on Feb. 11 and 12 and invites anyone interested to come learn more. The full text of the study, available for download at www.jewishinseattle.org/community-study/community-study-full-report, contains a vast trove of data where this article only touches the surface.

“It’s clear from this that this needs to be a starting point, not an ending point,” Dvorchik said. “It’s not a read through it once and you’ve got it all. There’s a lot, a lot, a lot of information there.”