By Michael Fox, Special to JTNews

Art challenges us with all manner of serrated edges, not least the paradox that beautiful and beloved works can be produced by loathsome — or at least deeply flawed — people.

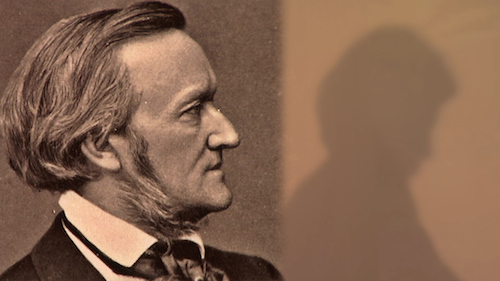

I find that it becomes easier over time to ignore the repugnant personalities and bad behavior and simply savor the music or painting or novel. A much more strenuous mental gymnastic was required for conductor Herrmann Levi, pianist Joseph Rubinstein, and producer Angelo Neumann to work with Richard Wagner for as long as they did.

Or so one gleans from “Wagner’s Jews,” a one-hour documentary made for European television and screening in the Seattle Jewish Film Festival. Perhaps of greatest interest to amateur psychologists, as well as classical music and opera buffs, the film provides valuable background and insight for viewers who aren’t steeped in Wagner’s soaring music or his callous writings.

Constructed from a prosaic mix of talking-head interviews, 19th-century photographs, and woodcuts, “Wagner’s Jews” attempts the daunting task of reconciling the loyalty and devotion that key Jewish collaborators felt toward Wagner with the demeaning anti-Semitism of his public writings (and, incredibly, in his direct dealings with Levi and Rubinstein).

Wagner’s animus toward Jews, expressed in a lengthy 1850 essay that he revised and reprinted nearly two decades later, could hardly have been based on his personal relationships with Jews. He owed much of his success to people like Giacomo Mayerbeer, a prominent German-Jewish composer who supported and touted the young Wagner, and the great Polish-Jewish pianist Carl Tausig, who sold patron certificates to fund construction of the opera house at Bayreuth.

Jews, Wagner wrote, were a “destructive foreign element” rather than a legitimate, organic part of German society or culture. Jewish artists were able to imitate but nothing more, he declared.

How could such first-rate musicians and valuable collaborators as Levi and Rubenstein work side by side with an unabashed racist? Well, to sum up the varied perspectives of the assembled historians and biographers: It’s complicated.

Classical music and opera were the cultural pinnacle of Europe in the late 1800s, and the undeniably gifted Wagner stood at the highest peak. My hunch is that Levi and Rubinstein were inspired and satisfied that they were applying their talents to the highest purpose. If they had to endure personal insults, humiliation and anguish — and there is ample evidence that they did — they would.

I don’t mind admitting that “Wagner’s Jews” demolished my ignorant assumption that the Nazis had simply embraced and promoted Wagner as an icon of superior Aryan accomplishment. In fact, the high- profile composer originated the theory that Jews were outsiders and parasites, providing a template for Hitler to build his platform of hatred and annihilation.

This crucial fact explains the fervid opposition to the proposed performance of Wagner’s work in Israel for the first time. The 2012 controversy provides a compelling contemporary frame for “Wagner’s Jews,” and invites us to grapple with the enduring conundrum of separating the creator from his or her creation.

Herrmann Levi and Joseph Rubinstein had the same problem, in spades.